The other day, I overheard an exchange between two young hostesses:

Hostess 1: Have you seen any good videos recently?

Hostess 2: You know, I’ve watched a lot, but I couldn’t tell you a single one I’ve seen.

Now, immediately, there’s all the standard takes:

Of course she doesn’t! Fragmented attention inhibits memory formation!

TikTok turns your brain to mush!

Young people are so stupid!

Addiction by design!

“On the scale between candy and crack cocaine, it’s closer to crack cocaine!!”

The world’s future is in the hands of these nitwits!

The ancients complained about the youth too, but this time it’s serious!

AHHHHHHHHHHHH!!!!!!!!!

After I told her all of those things, I realized that she wasn’t really upset about her TikTok amnesia. Because while TikTok might serve up content that is ostensibly entertaining, informative, or titillating, its true value is distraction. Thus, if you stand up after an hour of mindless TikTok scrolling and can’t remember anything that you saw, that’s a fair trade.

In Addiction by Design, Natasha Schüll describes a similar dynamic among compulsive slot gamblers. To an outsider, slots may seem like a game for low skill gamblers praying for a payout—like buying a lottery ticket but with more bells and whistles.

But when Schüll interviewed the players, the value they perceived was in the predictability of the experience, not in “winning.” They entered a trance-like state where they would keep pulling until they ran out of money. Casinos refer to this as gambling until “extinction.” Here’s how one player explained it:

I don’t care if it takes coins, or pays coins: the contract is that when I put a new coin in, get five new cards, and press those buttons, I am allowed to continue. So it isn’t really a gamble at all—in fact, it’s one of the few places I’m certain about anything.

By the same token, if a TikTok addict watches until extinction—til she can’t keep her eyes open or until her lunch break ends—then the value is simply in the absorption, and any entertainment or news gleaned is as relevant as winnings are to the slot player.

Obviously, modern life has all sorts of these pitfalls. As Sean Parker famously admitted, Facebook was consciously designed to hijack human desire: “It's a social-validation feedback loop…exactly the kind of thing that a hacker like myself would come up with, because you're exploiting a vulnerability in human psychology.”

Similarly, the idea of “empty calories” is a uniquely modern problem: food that doesn’t satiate, relationships that don’t comfort, information that doesn’t instruct. Our ancestors didn’t have to contend with the exploitation of their natural desires.

It can leave us feeling conflicted. It’s not quite nothing, but it’s not quite enough.

David Foster Wallace captured this strange dynamic between the confused consumer and the pleasure barons in his gonzo profile of the 1998 Adult Video Network Awards (basically The Oscars of pornography). Much like other modern industries that profit at the expense of their users, the porn industry at the time was publicly criticized but privately consumed. Here’s how Wallace describes the scene:

An observer gets the odd sense that the average fan here feels slightly ashamed of being slightly ashamed of his enthusiasm for porn, since the performers and directors now appear to have abandoned shame in favor of the steely-eyed exultation that always attends success in the great US market. Wherever else it is, porn is no longer in the shadows and slums. As [one producer’s] scarlet-clad crewman put it, “In a way, it’s kind of a drag. Now everybody’s watching it. We used to be rebels. Now we’re f— businessmen.”

25 years later, this dynamic of being “slightly ashamed of being slightly ashamed” is everywhere.

A fiancee discovers her husband-to-be has an entire VR pornography life, and her response is uncertainty: “It forced me to think about how I felt about it, because to me, like, okay, maybe my husband watches porn. That's fine, whatever, but the thought of him interacting with it in that way just feels like a bridge too far in my mind.”

Or we have the actor and writer Jason Segal reflecting on the sorry state of audience attention span that pressures artists to pander and entertain. Of course, he admits that he’s no better. He can’t even watch a 90 minute “masterpiece” without checking his phone for text messages. His verdict on our inability to enjoy art in any meaningful way?

“It’s a bummer.”

Or we have a piece like Andrew Sullivan’s 2016 essay “I Used to be a Human Being” that really captures the deleterious effect of the internet on attention and thus life. After years of obsessive blogging, he attends a silent retreat where he begins to see the world again:

On a meditative walk through the forest on my second day, I began to notice not just the quality of the autumnal light through the leaves but the splotchy multicolors of the newly fallen, the texture of the lichen on the bark, the way in which tree roots had come to entangle and overcome old stone walls. The immediate impulse — to grab my phone and photograph it — was foiled by an empty pocket. So I simply looked. At one point, I got lost and had to rely on my sense of direction to find my way back. I heard birdsong for the first time in years. Well, of course, I had always heard it, but it had been so long since I listened.

But of course, like all stories in this genre, this newfound ascetic insight doesn’t survive reentry into daily life:

The ubiquitous temptations of virtual living create a mental climate that is still maddeningly hard to manage. In the days, then weeks, then months after my retreat, my daily meditation sessions began to falter a little. There was an election campaign of such brooding menace it demanded attention, headlined by a walking human Snapchat app of incoherence. For a while, I had limited my news exposure to the New York Times’ daily briefings; then, slowly, I found myself scanning the click-bait headlines from countless sources that crowded the screen; after a while, I was back in my old rut, absorbing every nugget of campaign news, even as I understood each to be as ephemeral as the last, and even though I no longer needed to absorb them all for work.

Then there were the other snares: the allure of online porn, now blasting through the defenses of every teenager; the ease of replacing every conversation with a texting stream; the escape of living for a while in an online game where all the hazards of real human interaction are banished; the new video features on Instagram, and new friends to follow. It all slowly chipped away at my meditative composure. I cut my daily silences from one hour to 25 minutes; and then, almost a year later, to every other day. I knew this was fatal — that the key to gaining sustainable composure from meditation was rigorous discipline and practice, every day, whether you felt like it or not, whether it felt as if it were working or not. But the world I rejoined seemed to conspire to take that space away from me. “I do what I hate,” as the oldest son says in Terrence Malick’s haunting Tree of Life.

Of course, that’s not a Terrence Malick original. It’s St. Paul: “For the good that I will to do, I do not do; but the evil I will not to do, that I practice.”

Although, I wonder how many of us truly feel like St. Paul. I wonder if we’re not closer to St. Augustine in his Confessions: “Lord, make me chaste—but not yet.”

I had a conversation with

that’s really stuck with me over the past months. She’s more tech-ascetic than I am, and I was asking her about the idea that people often, with a knowing wink, admit that their phones are “making them stupid” or that “they’re an addict” and she cut in:They are, and it is. If you think you're an addict, you definitely are. Because a lot of addicts don't even think they're addicts. They're in denial. So if you think you're addicted, then, Yes, you are very addicted, and you need to deal with it, because you're not going to be able to affect any difference in the kingdom through your addiction.

Unfortunately, this process of rooting out idols in your heart and letting God into those places is a long one. What’s more, she said, it’s boring. In other words, everybody wants to be transformed. Nobody wants to change.

The novelist Zadie Smith is not religious, but she used almost identical language when explaining why she doesn’t own a smartphone:

So when I get on a train in the morning and I look down a carriage and I can look down half a mile of carriage, there isn't a single person who is looking up from their phones. It's total. So that was my question. Like what happens when it's everybody?

I cannot imagine. I cannot imagine what my mind would be, what my books would be, what my relationships would be, what my relationship with my children would be.

Until last year, my husband also didn't have a smartphone. And so we were 47 or whatever, we've been doing this for a while. About once a year, there would be an absolute travel disaster. Like, just we're at a party at three in the morning. There's no way to get home. Forget about it.

Walk five miles. Like, disaster. Once a year. And every time it happened, I would think, that was bad. But is it as bad as having my very consciousness colonized every moment of the day? And I'd be like, no. Definitely no competition.

Does this critique hit close to home for you? It does for me.

The trouble is, we usually diagnose at the level of reason—“Constant stimulation is not good for me; I am addicted to my phone; I shouldn’t eat that”—but the actions are unconscious.

We are pontificating when we need to be recolonizing.

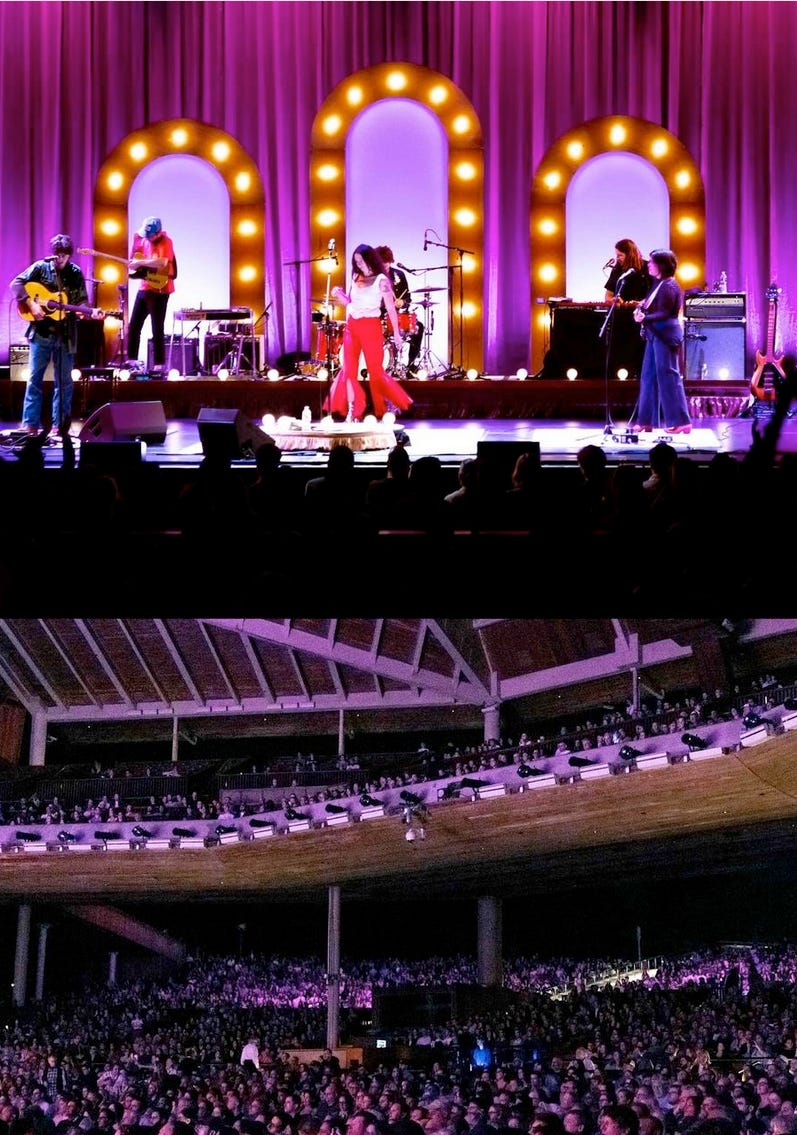

I recently went to one of the best concerts I’ve ever attended: a Waxahatchee show at Wolf Trap right near me. The music was great, her stage presence was palpable, and it was a perfect summer night.

And I had the thought, “It’s hard to appreciate this.”

I can’t get physically comfortable, so I keep standing up, sitting down, and shifting around. I don’t know every song, and my mind is wandering. The people near me are distracting. I’m here, everything is perfectly laid out for me, but I can’t just enjoy it.

It was a helpful reminder.

Most of the time, I think of my biggest challenges as issues of access. I don’t have enough money, time, status, etc. to do what I want. The corollary to this is what the Swiss psychologist Marie-Louise von Franz called the "provisional life." The idea being “that one is not yet in real life. For the time being, one is doing this or that… [but] there is always the fantasy that sometime in the future the real thing will come about.”

The trouble is, I’m usually focused on the technical problem of how to acquire a desired thing. But then, like at the concert, there is the more complex problem of taming your desires so that you can actually enjoy the thing itself.

Jonathan Haidt likened the relationship between our conscious, planning mind and our unconscious, intuitive desires to that of a rider and an elephant. The rider can make plans or excuses or warnings.

But as you might guess, the elephant is the more powerful of the two.

In his specific area of interest, moral reasoning, he calls this framework the social intuitionist model. He argues that our inner elephant uses heuristics to navigate the world, and while the rider can sometimes shape the elephant’s course, the rider often ends up functioning as a lawyer, offering post hoc justifications for the elephant’s behavior.

For instance, you may hear of a story from XYZ news, an outlet that you despise. You feel an immediate flash of disgust upon hearing their name. Your elephant is primed to disagree with these journalistic hacks. Sure enough, after just a few words, your rider is already providing all sorts of examples of sloppy reasoning, biased framing, and confirmation that, yes indeed, XYZ is a wretched hive of scum and villainy.

If you’ve ever gotten in a spat with your spouse (I haven’t personally), you know the feeling of saying something untrue in the heat of the moment and later having to apologize. The elephant was mad, and the rider was covering for him.

And while you can quibble with Haidt’s anthropology, I find the analogy a helpful one. If you want to create change, the challenge is not coming up with clever arguments to convince yourself or others. Those are rider solutions to elephant problems. The rider’s looking for a plan, deadlines, and targets, but the elephant requires something more subtle.

Haidt’s answer is cognitive behavioral therapy, Prozac, and meditation. These are all methods aimed at the elephant, hoping to counteract maladaptive thought patterns and chemical imbalances.

James Clear might advise the elephant be trained by healthy habits and prescribe the four laws of Behavior change: (1) make it obvious, (2) make it attractive, (3) make it easy, and (4) make it satisfying.

This requires patience because the elephant can be slow to change:

Your outcomes are a lagging measure of your habits. Your net worth is a lagging measure of your financial habits. Your weight is a lagging measure of your eating habits. Your knowledge is a lagging measure of your learning habits. Your clutter is a lagging measure of your cleaning habits. You get what you repeat.

Spiritually, you might say the difference between treating a rider and an elephant is the difference between a sermon and a sacrament. Both are important, but clearly having access to infinite amounts of spiritual content hasn’t made us all saints.

So that’s the challenge: how do we maintain the patience and subtlety necessary to train the elephant? Of course, I don’t have a tidy fix for all of this, but perhaps I can offer a couple of ideas—rider to rider—that I’ve found helpful.

Put Flow Before Ease

In his famous book, Flow, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi wrote:

Contrary to what we usually believe, the best moment in our lives are not the passive, receptive, relaxing times—although such experiences can also be enjoyable, if we have worked hard to attain them. The best moments usually occur when a person’s body or mind is stretch to its limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult or worthwhile…

Such experiences are not necessarily pleasant at the time they occur. The swimmer’s muscles might have ached during his most memorable race, his lungs might have felt like exploding, and he might have been dizzy with fatigue—yet these could have been the best moments of his life.

Perhaps this helps explain the common phenomenon of older parents fondly recalling the early days of parenting. It may be that they have rose-colored glasses looking back and simply don’t remember how hard it was. But it may be that they are proud of how tough those years were.

And this has corollaries all over the place. A great marriage is strengthened through the storms it weathers. A muscle only grows through strain. A great book requires struggle to appreciate. As St. Ambrose of Milan put it describing the spiritual life:

Those who haven’t gone down to the track don’t smear themselves with oil, nor get covered with dust. Trouble comes only to those on their way to glory. The perfumed spectators prefer to watch, not to join the struggle, nor to endure the sun, the heat, the dust, and the rain.

The hard times aren’t incidental to the good ones. They’re essential.

Don’t Disturb Your Peace

In Our Thoughts Determine Our Lives, Elder Thaddeus writes:

A lifetime of experience is needed to reject evil and turn toward goodness so that nothing in this world can lead us astray from the right path. This is why St. Isaac the Syrian says, “Preserve your inner peace at all costs and do not trade it for anything in this world.”

This is where the rider can be helpful. We have natural desires for activity or information or social connection that are often hacked by our modern world. And we need to recognize those traps and, as

says, draw our line in the sand and stick to it:Personally, for example, I have drawn my lines at smartphones, “health passports,” scanning QR codes, or using state-run digital currency. I limit my time online, use a “dumb phone” instead of a smartphone, turn off the computer on weekends, and steer well away from sat navs, smart meters, Alexas, or anything else that is designed either to addict me or to harvest my information...

Drawing those personal lines in the sand, and then holding to them, has to be a personal project for everyone. We all have to decide where we are prepared to stand, and how far we can go.

Drawing that line requires wisdom, but once you’ve drawn it, you need to be careful to curate an environment without so many triggers. This is not a new problem.

In Augustine’s Confessions, we read of Alypius who had resolved to no longer attend gladiatorial games. Then his old friends came along, and temptation ensued:

He was one day met by chance by various of his acquaintance and fellow-students returning from dinner, and they with a friendly violence drew him, vehemently objecting and resisting, into the amphitheater, on a day of these cruel and deadly shows, he thus protesting: “Though you drag my body to that place, and there place me, can you force me to give my mind and lend my eyes to these shows? Thus shall I be absent while present, and so shall overcome both you and them.”

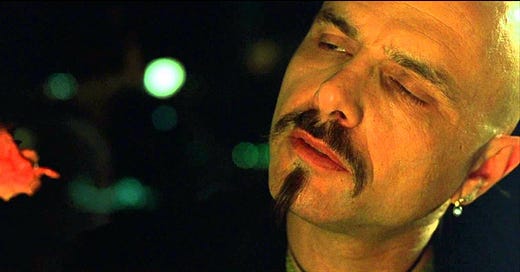

They hearing this, dragged him on nevertheless, desirous, perchance, to see whether he could do as he said. When they had arrived there, and had taken their places as they could, the whole place became excited with the inhuman sports. But he, shutting up the doors of his eyes, forbade his mind to roam abroad after such naughtiness; and would that he had shut his ears also! For, upon the fall of one in the fight, a mighty cry from the whole audience stirring him strongly, he, overcome by curiosity, and prepared as it were to despise and rise superior to it, no matter what it were, opened his eyes, and was struck with a deeper wound in his soul than the other, whom he desired to see, was in his body; and he fell more miserably than he on whose fall that mighty clamor was raised, which entered through his ears, and unlocked his eyes, to make way for the striking and beating down of his soul, which was bold rather than valiant hitherto; and so much the weaker in that it presumed on itself, which ought to have depended on You.

For, directly he saw that blood, he therewith imbibed a sort of savageness; nor did he turn away, but fixed his eye, drinking in madness unconsciously, and was delighted with the guilty contest, and drunken with the bloody pastime. Nor was he now the same he came in, but was one of the throng he came unto, and a true companion of those who had brought him there. Why need I say more? He looked, shouted, was excited, carried away with him the madness which would stimulate him to return, not only with those who first enticed him, but also before them, yea, and to draw in others.

Alypius’s progression from overconfidence to embracing a sinful passion is a familiar story. When faced with a decision, sometimes an unusual question can reframe an issue.

Why not try St. Isaac’s: “Does this disturb my peace?”

Caveat Adorator

Perhaps David Foster Wallace’s best-known piece is his “This is Water” speech. It’s a bit banal now, but since I referenced him earlier in the context of depravity, it’s worth returning to some of his more inspirational words (emphasis is mine):

Here’s something else that’s weird but true: in the day-to-day trenches of adult life, there is actually no such thing as atheism. There is no such thing as not worshiping. Everybody worships. The only choice we get is what to worship. And the compelling reason for maybe choosing some sort of god or spiritual-type thing to worship–be it JC or Allah, be it YHWH or the Wiccan Mother Goddess, or the Four Noble Truths, or some inviolable set of ethical principles–is that pretty much anything else you worship will eat you alive.

If you worship money and things, if they are where you tap real meaning in life, then you will never have enough, never feel you have enough. It’s the truth. Worship your body and beauty and sexual allure, and you will always feel ugly. And when time and age start showing, you will die a million deaths before they finally grieve you. On one level, we all know this stuff already. It’s been codified as myths, proverbs, clichés, epigrams, parables; the skeleton of every great story. The whole trick is keeping the truth up front in daily consciousness.

Worship power, you will end up feeling weak and afraid, and you will need ever more power over others to numb you to your own fear. Worship your intellect, being seen as smart, you will end up feeling stupid, a fraud, always on the verge of being found out. But the insidious thing about these forms of worship is not that they’re evil or sinful, it’s that they’re unconscious. They are default settings.

They’re the kind of worship you just gradually slip into, day after day, getting more and more selective about what you see and how you measure value without ever being fully aware that that’s what you’re doing…

Our own present culture has harnessed these forces in ways that have yielded extraordinary wealth and comfort and personal freedom. The freedom all to be lords of our tiny skull-sized kingdoms, alone at the center of all creation. This kind of freedom has much to recommend it. But of course there are all different kinds of freedom, and the kind that is most precious you will not hear much talk about in the great outside world of wanting and achieving…. The really important kind of freedom involves attention and awareness and discipline and being able truly to care about other people and to sacrifice for them over and over in myriad petty, unsexy ways every day.

You must be careful what you worship, but worship is often more instinctive than intellectual. If, as he says, the trick is keeping the truth up front, to keep God as the object of worship, rituals are needed to guide the elephant along.

Thus, I’ve found great relief in spiritual disciplines that simply tell you what to do, how to pray, when to fast. It takes control out of the rider’s hands. In my own little corner of Orthodox converts, seekers often show up with lots of questions: “Which Patriarch are we in communion with? Why is the clergy all male? What’s with all the Theotokos stuff?”

And if they keep coming, more often than not, those questions don’t get precisely answered, they just fade away. The beauty of the Liturgy and power of the practices shape the elephant such that, eventually, the rider just gets on board with the new direction.

Of course, it’s good to keep perspective on all of this. Our elephants won’t change in a day, but that doesn’t mean we should despair. Alypius’ lapse, however dramatic, wasn’t catastrophic. He went on to become the Bishop of Tagaste.

The path is simple enough, though hardly easy. As St. Theophan the Recluse advised, “If you have sinned, acknowledge the sin and repent. God will forgive the sin and once again give you a new heart…and a new spirit (Ez. 36:26). There is no other way: Either do not sin, or repent.”

But as Elder Thaddeus said, it takes a lifetime of prayer and repentance to reject evil and turn toward goodness. So in all seriousness, we must “lay aside every weight, and the sin which so easily ensnares us,” and in all jest, we must strive to ride our elephants with the ease and delight of this young man.

DFW?? Waxwhatchee?? ‘I Used to Be a Human Being’?? Mihalyi Csikszentmihalyi?? Augustine?? How have I not been reading this publication??

This is a great piece. Thanks!