Nicholas Carr Is Not "The Guy"

How Spy Kids 3-D: Game Over Explains Our Technological Moment

There’s a moment about halfway through Spy Kids 3-D: Game Over when our protagonists, Juni and Carmen, realize they’re in trouble. These intrepid kids are trapped inside of a video game, but they believe that someone, “The Guy,” can beat the unwinnable level that they are stuck on and save the day.

They are arguing over who “The Guy” might be when all of a sudden Elijah Wood appears in a flash of bright light, exuding confidence and laying out a plan to claim the “bounty fit for ten kings.” One of the punk villain kids, clearly awestruck, says, “Now he’s definitely the guy.”

But when “The Guy” charges into the booby trapped room, he is zapped immediately, and ten seconds later, he has died and disappeared. (Remember, they’re inside of a video game). In about 2 minutes and 30 seconds, the group goes from fearing they’ll never find “The Guy,” to relief that they’ve “definitely” found him, to greater despair than they had at the start.

Not to get too deep on my Spy Kids 3-D exegesis, but this scene seemed like unnecessary comic relief when I was a kid. I now see that it’s a critical plot point that illustrates the hero’s temptation to shirk responsibility in the face of daunting challenges.

So long as Juni is holding out hope for some “The Guy” ex machina solution, he doesn’t take responsibility for beating the “unwinnable” level. He wants this problem to be solved by someone else. Once “The Guy” comes in glory and dies in humiliation, Juni realizes it’s up to him.

This is the best way I can explain how I felt reading Nicholas Carr’s new book Superbloom. I was hoping he’d be “The Guy,” and I am sad to report, he is not.

I will start by saying that The Shallows and The Glass Cage remain two of the best books on the internet, digital technology, and their consequences for us as humans. They are books that formed and inspired me. I have spent the last ten years watching digital technology steadily grow in power and scope, and I have often wondered, “Where is Nicholas Carr?” I much desired to hear from him.

So when I got my review copy of Superbloom: How Technologies of Connection Tear Us Apart, I was eager to read it, and I was primed to like it. Perhaps my expectations were too high. In hindsight, I would’ve been better off just reading his recent articles rather than the whole book.

Carr is still a gifted prose stylist, and there are some well-done sections. For instance, he describes how access to the mail changed people’s lives:

If, as William Wordsworth suggested, the origin of poetry lies in “emotion recollected in tranquility,” then the writing of a letter brought at least a little of the poetic sensibility into people’s otherwise busy days. The reading of books and journals had given individuals a means of constructing a distinct intellectual self. The writing of letters gave them a means of constructing a distinct experiential self.

He goes on to explain how the increasing speed of messages changed the experience of reading:

Messages streaming through a screen, one overlapping the other, need to be taken in at a glance, decoded by the eye with minimal cognitive effort or attentional drain. Reading becomes less a matter of following a line of thought and more a matter of recognizing a pattern. Writing shifts from the linear and literal to the visual and symbolic.

But you might notice that these examples are more a clever framing of familiar territory rather than breaking new ground. If you are the kind of person who is aware of Carr and already interested in this topic, you will spend much of the book saying, “And?”

For instance, his description of social media’s addictive qualities is not new: “What fills online feeds, research shows, is content that stirs strong emotions and provokes symptoms of ‘physiological arousal’…Whether we realize it or not, social media churns out information that’s been highly processed to stimulate not just engagement but dependency.”

He provides some interesting historical context, quoting the German social critic Theodor Adorno in 1951, to illustrate a common point about how technological advance prizes cold efficiency: “If time is money, it seems moral to save time, above all one’s own, and such parsimony is excused by consideration for others.” Thus, Carr concludes, “The discursive, unhurried style of the personal letter, Adorno feared, was giving way to the blunt style of the bulletin.”

At times, I think he’s flat wrong: “When Zuckerberg, in 2022, announced that Facebook was changing its corporate name to Meta Platforms and would embark on the construction of an all-encompassing virtual world called the metaverse, everyone yawned. The metaverse had been around for years, and we were in it.”

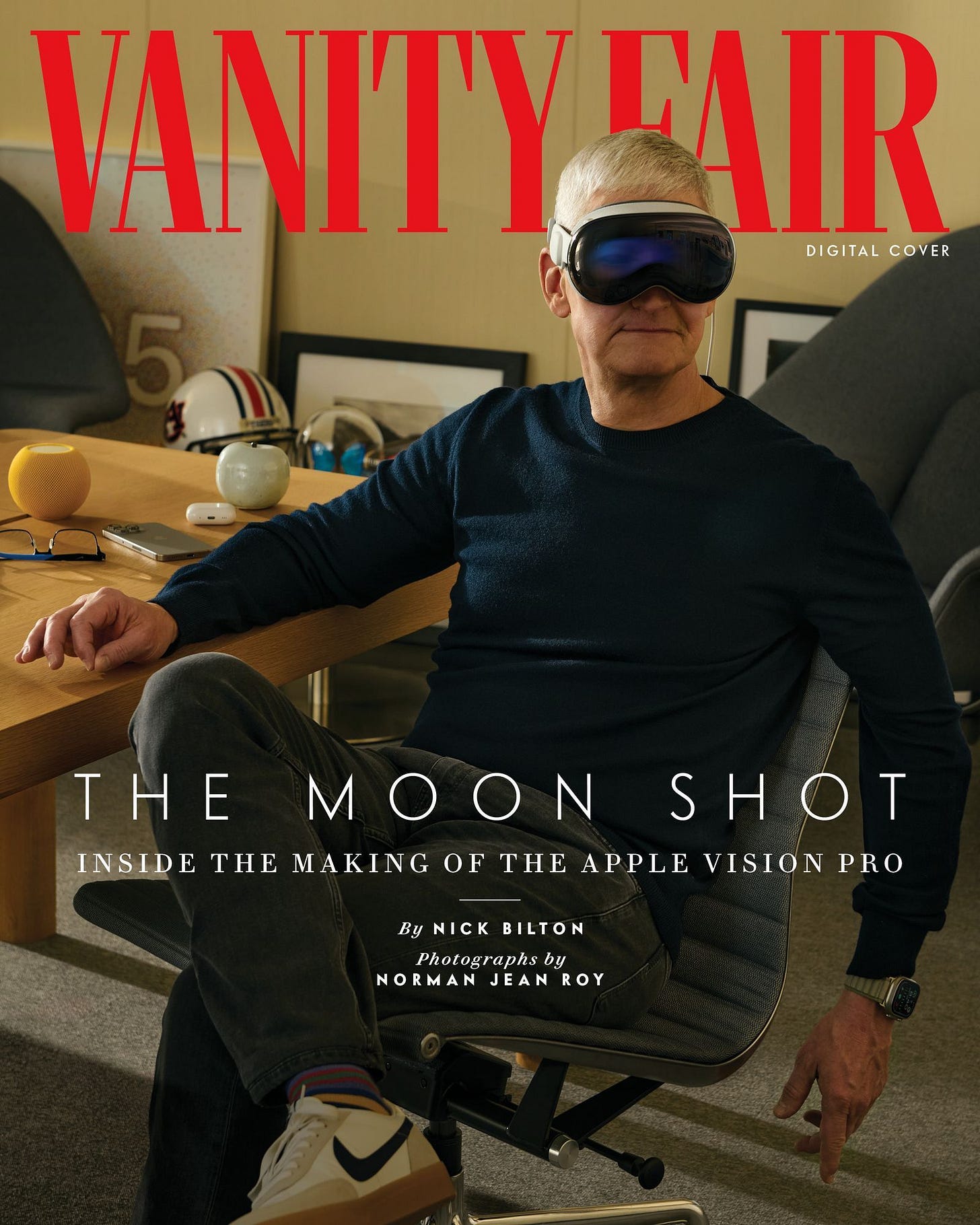

Actually, I think Tim Cook wearing these goggles is meaningfully different from people using phones and computers, and this photo is a punchline for good reason. To conflate scrolling on your phone with the goofy avatars in the metaverse seems imprecise for a tech critic.

His politics appear to be Never Trump, and they undermine his credibility. He continually presents everything wrong with the internet in partisan terms: J6, Pizzagate, Donald Trump’s 2016 election win due to Russian misinformation, Elon Musk’s X as a censorious, debased platform.

Though his sketch of the history of media regulation is helpful background, his partisanship unintentionally makes the case against entrusting the government with moderating content or seriously altering platforms. He never mentions The Twitter Files or Covid, two instances that illustrate how these problems cannot be neatly reduced to partisan politics.

His silence implies that he believes the only problem with our status quo is who owns X and who is in the Oval Office. These arguments will soothe a certain slice of the Left, but I doubt they will persuade many.

This leads me back to Spy Kids and how Nicholas Carr is not “The Guy.”

If you, like me, have been waiting on someone to help make sense of the modern internet, you can stop waiting. At least, that’s my takeaway.

The book’s conclusion—not the intro, the conclusion—says, “Maybe salvation, if that’s not too strong a word, lies in personal, willful acts of excommunication—the taking up of positions, first as individuals, and then, perhaps, together, not outside of society but at society’s margin, not beyond the reach of the informational flow but beyond the reach of its liquefying force.”

Resistance to the Machine? Yes, Paul Kingsnorth, Matthew B. Crawford, Grant Martsolf, and Peco and Ruth Gaskovski have a thing or two to say on that.

Carr concludes where most engaged readers on this topic begin, and he seems unaware of the state of the current discourse in this space. I guess his target audience is a bit older, left-leaning, and he’s trying to catch them up on the last decade rather than push the envelope with these Against the Machine types. I suppose I was hoping for something more than that.

The truth is, I’m sad that Superbloom wasn’t better (so sad that I am processing it indirectly via a kids B-movie). But I’m grateful for the wake-up call. It’s time to stop waiting around for “The Guy.” It’s time to act.

If I want my community to be stronger, I can quit kvetching about how everyone’s busy. If it requires spending an hour a week scheduling and texting to follow up, then I can either do that, come up with a better system, or shut up about it.

If I think social media is toxic, I can leave and ask my friends to follow. Perhaps Jonathan Haidt is singlehandedly turning the tide, but after reading Superbloom, I am even more skeptical any meaningful change will come from the top down. I take hope in the grassroots exit I am seeing from some of my peers and the community on Substack.

How can I get spy friends

The Spy Kids reference is a deep cut. My jaw hit the floor when I saw Elijah Wood staring at me from my inbox.