Marriage as a Masterpiece

In our products as in our relationships, there is a dearth of craftsmanship.

I read an essay last year, and I’m still not sure if the author, a woman named Grazie Sophia Christie, is doing satire or memoir:

When I was 20 and a junior at Harvard College, a series of great ironies began to mock me. I could study all I wanted, prove myself as exceptional as I liked, and still my fiercest advantage remained so universal it deflated my other plans. My youth.

…

So naturally I began to lug a heavy suitcase of books each Saturday to the Harvard Business School to work on my Nabokov paper. In one cavernous, well-appointed room sat approximately 50 of the planet’s most suitable bachelors. I had high breasts, most of my eggs, plausible deniability when it came to purity, a flush ponytail, a pep in my step that had yet to run out. Apologies to Progress, but older men still desired those things.

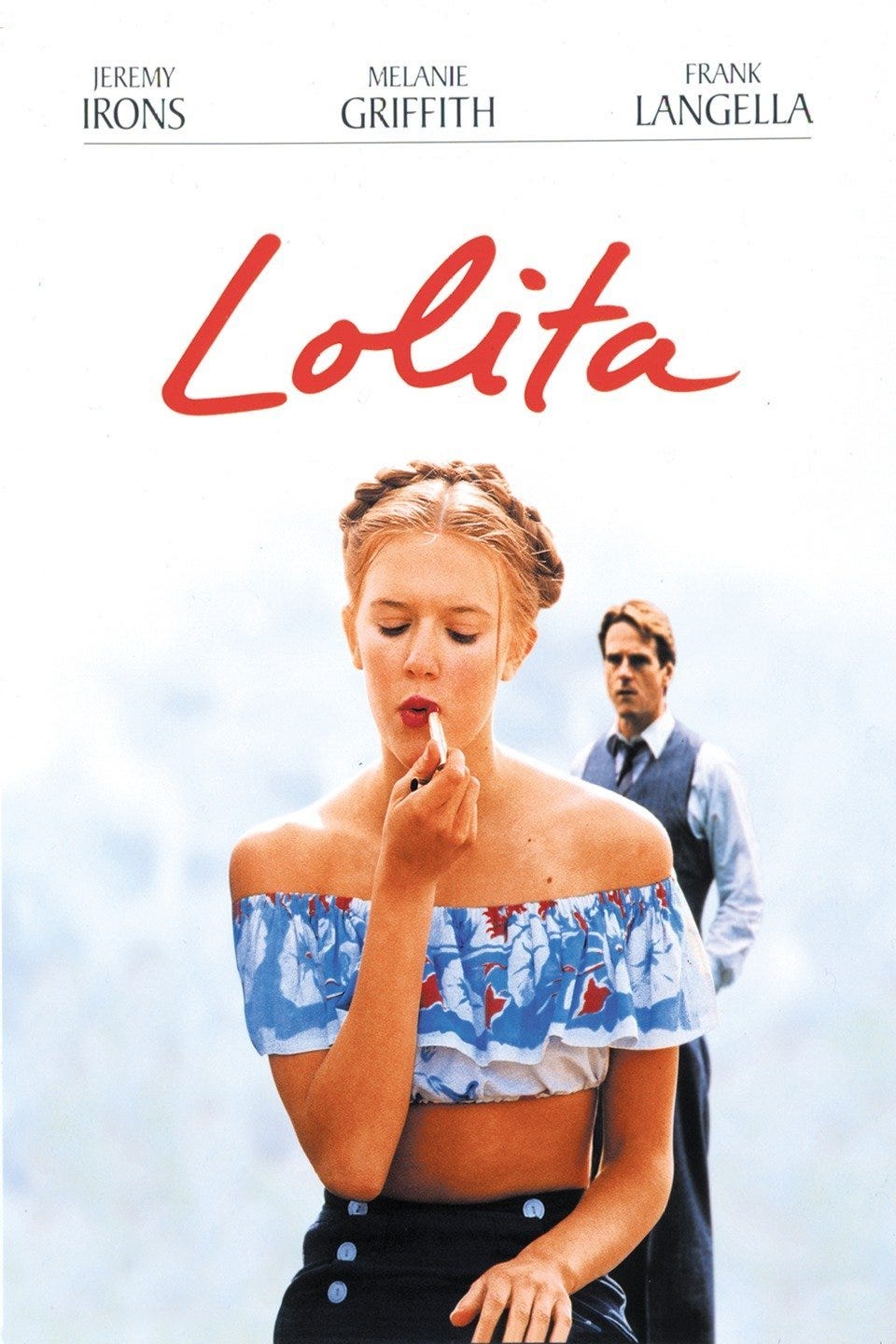

She goes on to say how Lolita, Nabokov’s famous book about a man obsessed with young girls, is one of her favorites.

She ends up marrying an eligible HBS man ten years her senior. This creates some unusual dynamics:

My husband isn’t my partner. He’s my mentor, my lover, and, only in certain contexts, my friend. I’ll never forget it, how he showed me around our first place like he was introducing me to myself: This is the wine you’ll drink, where you’ll keep your clothes, we vacation here, this is the other language we’ll speak, you’ll learn it, and I did. Adulthood seemed a series of exhausting obligations. But his logistics ran so smoothly that he simply tacked mine on. I moved into his flat, onto his level, drag and drop, cleaner thrice a week, bills automatic.

Of course, this approach has its drawbacks:

There are only so many times one can say “thank you” — for splendid scenes, fine dinners — before the phrase starts to grate. I live in an apartment whose rent he pays and that shapes the freedom with which I can ever be angry with him. He doesn’t have to hold it over my head. It just floats there, complicating usual shorthands to explain dissatisfaction like, You aren’t being supportive lately.

As if this weren’t all strange enough, she published a piece the year prior about a different boyfriend ten years her senior who dumped her when she was 20:

My own inglorious adolescence ends with me dumped, over brunch, at twenty. He has a strong jaw which dazes and a soft birthmark, near the mouth. He is ten years older than me.

In story form, this all sounds pretty absurd. The most common takes were “You didn’t marry old, you married rich!” and “I hope you enjoy getting dumped for a younger woman!” No matter your perspective, it was a hate read.

The funny thing is, she’s really just offering the anecdotal version of the modern dating talking points. Hypergamy, sexual “market value,” body count, bank account. Women’s sexual availability traded for man’s money and (sometimes feigned) attention. This sort of thinking is prevalent in think pieces that supposedly decode gender relations by reducing them to what

calls “monocausal evopsych justifications.” She takes this lazy thinking to task.And that’s the part about Christie’s essay that I can’t quite fathom. She is from a prominent Catholic family in Florida (her mom has a show on EWTN), yet she is so cold and cynical in approaching her marriage. She explicitly and unflinchingly frames relationships in transactional, numerical terms: “The truth is you can fall in love with someone for all sorts of reasons, tiny transactions, pluses and minuses, whose sum is your affection for each other, your loyalty, your commitment.”

This approach to dating and marriage is often described as “consumeristic.” It reduces marriage to a “what’s in it for me” mindset and “objectifies” your potential spouse. And of course, that’s bad enough.

But recently, I’ve thought about how young people today have a different relationship to consumption than their grandparents did, and that might shape their expectations about relationships on a subconscious level.

Modern consumption is characterized by cheap, disposable, and interchangeable goods. Nothing is built to last. Obsolescence is either planned by Apple or guaranteed by shoddy workmanship. When things do break down, it’s often both easier and cheaper to just buy a replacement rather than fix the old one. Our cars are too complicated to tinker with, and our Temu items aren’t worth the bother.

We are not accustomed to darning, sewing, stitching, sanding, sharpening, soldering, you name it. If we are consumers, we are often wasteful, shortsighted ones. So perhaps it makes sense we’d struggle to commit to a spouse or mend a rift when it came along. We’re accustomed to a lifestyle that rewards impulsivity and convenience, not deliberation and care.

But we all sense something missing. When a friend asks, “Where’d you find this?” there’s always a little embarrassment when the answer is, “Oh, I just got it off Amazon.” Celebrities may be able to cycle through perpetual romantic flings, but when the rest of us mortals attempt to replicate this strategy—either via AI girlfriends, pornography, or dating apps—it leaves us empty. In our products as in our relationships, there is a hunger for craftsmanship.

As a young newlywed, I got some helpful advice: “Great marriages aren’t found; they’re built.” If building and creation is a better metaphor for relationships than consumption, then perhaps studying artists and craftsman would be more helpful than listening to yet another pop evolutionary psychologist opine on mating strategies.

Rather than viewing your marriage as a product that you will use and dispose of at your convenience, you might think of it as your magnum opus, a masterpiece you will be working on for your whole life.

The Temu-ification of Relationship

“Imaginary evil is romantic and varied; real evil is gloomy, monotonous, barren, boring. Imaginary good is boring; real good is always new, marvelous, intoxicating.” - Simone Weil

Steven Pressfield, who at times has been both an addict and an artist, writes about the relationship between the two. Whereas the artist aspires to create something, the addict becomes the spectacle themself:

The addict’s life may appear exciting—sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll—but is actually boring because “it’s so predictable. The lies, the evasions, the transparent self-justification and self-exoneration.” The artist’s life appears boring—just a writer sitting at his desk—when in fact it’s thrilling, “it’s Game of Thrones going on inside your head.” You’re getting traction, you’re going somewhere.

When James Taylor reflected on the years he spent hooked on heroin, he simply said, “the thing about drugs with me is that they were eventually boring and when they weren't boring it was a humiliating, stupid accident. In the end, it was simply too narrow. I felt as though I lived on a postage stamp.”

Rather than do the hard, internal work of creation, addicts take the easy route of public display and dissipation. Their life becomes the chaotic, entertaining show rather than their art.

We live in a society that encourages exhibitionists. As

put it:“If a tree falls in the forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?” could be re-written today as, “If no one but me witnesses my life and experiences, does my life even matter?” In our modern age, if things don’t happen publicly, for an audience, we cease to believe they happened at all.”

There is a pressure for everything to be displayed and thus simplified and compressed. Our communication is bullet points, headlines, summary—style is superfluous, even an obstruction. Netflix is ordering writers and directors to make the content so simple that it can be watched while folding laundry. Justine Bateman explains to The Hollywood Reporter:

I’ve heard from showrunners who are given notes from the streamers that “This isn’t second screen enough.” Meaning, the viewer’s primary screen is their phone and the laptop and they don’t want anything on your show to distract them from their primary screen because if they get distracted, they might look up, be confused, and go turn it off. I heard somebody use this term before: they want a “visual muzak.”

This leads to explicitly recapping plot points and announcing character intentions in Netflix’s new releases:

“We spent a day together,” [Lindsay] Lohan tells her lover, James, in Irish Wish. “I admit it was a beautiful day filled with dramatic vistas and romantic rain, but that doesn’t give you the right to question my life choices. Tomorrow I’m marrying Paul Kennedy.” “Fine,” he responds. “That will be the last you see of me because after this job is over I’m off to Bolivia to photograph an endangered tree lizard.”

In e-commerce, Temu, the Chinese competitor of Amazon, is perhaps the clearest example of this garish efficiency. Inevitably, their ads feature some risqué model: a cheap trick to grab your attention and then they offer you a cheap product. There is no hidden craftsmanship, human touch, or expected durability. There’s no brand loyalty, no connection to a human creator. It’s just an unashamed appeal to your base instincts all the way around.

By contrast, a well-made product keeps unfolding the more time you spend with it. You might purchase it because you trust the brand (or better yet, the artisan himself), but over time, you’re impressed by its durability, the way the cuffs match the collar when you roll them back, the perfect angle of the rocking chair seat.

This sort of appreciation requires subtlety, taste, and study.

A craftsman marriage would be filled with moments whose gravity would be lost on a viewer. Unlike The Irish Wish, you wouldn’t have to explain everything you’re saying and doing! Instead, a certain word, touch, or silence would have a subtext only known to the two of you. The visible would just be the tip of the iceberg, and this deepening would be a constant process.

You wouldn’t approach an epic like Ulysses and expect to get it all on the first pass. You would return over and over again, finding new delights with each visit, giving your full attention each time. And that’s to understand a static book, not an ever-changing person!

Death to Efficiency

“If you’re efficient, you’re doing it the wrong way. The right way is the hard way. The show was successful because I micromanaged it—every word, every line, every take, every edit, every casting. That’s my way of life.” - Jerry Seinfeld

Ian Fleming, the author of James Bond, was apparently, by design, an unhappy writer. He would intentionally choose a backwater, rundown area he didn’t like and then hole up for two weeks until his book draft was done. The unpleasant town spurred him to work quickly.

Though this story may be apocryphal (I’ve heard other stories of Fleming’s writing strategy that are less masochistic), it illustrates a common sentiment among artists: lasting success requires discipline and boredom. Discipline to do the work, boredom to let things percolate. The ratio of suffering to discipline varies by artist.

Anne Lamott recounts in Bird by Bird how a friend of her says, “It's not like you don't have a choice, because you do — you can either type, or kill yourself.” Other writers are a little less dour. Michael Lewis, the author of The Big Short and Moneyball, says writing makes him happy, and his kids report that he laughs all day as he writes.

But a common thread is a willingness to consistently work even when it feels like nothing is happening. Many writers have explicit rules like: “You can write or do nothing.” Anne Lamott finds inspiration elusive but concludes, “All I know is that if I sit there long enough, something will happen.”

Likewise, a craftsman expects years of apprenticeship and mundane practice on the road to mastery. If he’s unwilling to do that, he will become a dilettante: always flitting from one thing to another, chasing something new or easy, never creating anything substantive or original.

And we are all tempted by novelty today. There’s too much to read, watch, listen to, visit etc. etc. If something doesn’t grab us immediately, whether a restaurant, acquaintance, or book, it’s on to the next and no looking back. And there’s obviously a stimulation to living like that, but it resembles the seeking behavior of an addict more than the contemplation of a craftsman.

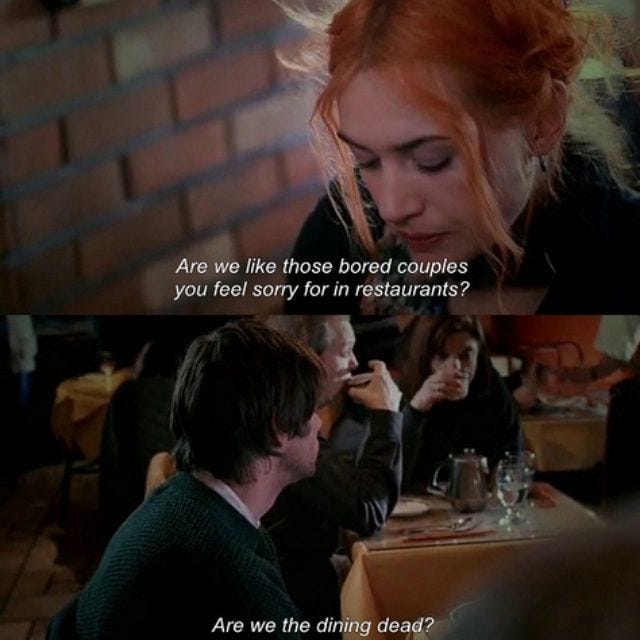

The boring middle-aged couples with nothing to talk about is a pop culture trope: Jim and Pam on The Office, Ted and Tracey in How I Met Your Mother, Joel and Clementine in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.

But to extend our artist analogy, I’d liken that to the writer who finds something that works and then churns out variations on that theme over and over. A Hardy Boys marriage. That may work for you, it may be a perfectly serviceable method, but it need not be a universal sentence.

There are clearly marriages that grow and improve across a lifetime, just like artists do. Is The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan better than Blood on the Tracks? Is Sgt. Peppers better than Revolver? They’re just different. If you listen to Paul Simon get interviewed, he has a confidence that he will never run out of ideas, and if you look at his discography, you will see that he has never stopped experimenting (on into his 80’s).

It's worth adding that the actual workflow of productive creatives is far more mundane than you might expect. If you watch Peter Jackson’s documentary on The Beatles, you see some sudden breakthroughs—“Get Back” mostly comes together when Paul is jamming for a few minutes while waiting for John—but the rest of the album comes in fits and starts.

At one point, George is trying to figure out the lyrics for “Something” and admits that he’s been stuck for six months on the lyric “attracts me like a pomegranate.” John advises, “Just say whatever comes into your head each time. ‘Attracts me like a cauliflower,’ until you get the word, you know?” Eventually, they get to the lines we know: “Something in the way she moves me, attracts me like no other lover.” But it’s a grind to get there.

Showing up day in and day out, when you have lots to say or nothing to say, when you’re feeling good or feeling bad, obviously bears fruit for marriages as well as The Beatles. It’s the only way to find things you weren’t looking for: a brilliant idea, a surprising self-revelation, a compliment you forgot to pass along. That requires a certain consistency of setting aside time without a plan or agenda.

Few creatives with long careers work in infrequent bursts of activity, just like few stable marriages attempt to fit a year’s worth of romance and conversation on the anniversary dinner. Longevity comes when the day-to-day practice and improvement becomes the steady, satisfying part of the whole thing and any breakthroughs and accolades are gravy.

The Work Is the Reward

“Publication is not all that it is cracked up to be. But writing is. Writing has so much to give, so much to teach, so many surprises. That thing you had to force yourself to do—the actual act of writing—turns out to be the best part.” -Anne Lamott

Lamott tells her students that likely none of them will get published and even fewer will make any kind of living, but they should still write for the sake of the work itself. Even the more melancholic writers know that when they are working, they can feel “better and more alive than they do at any other time.”

Here's where artists might have something valuable to teach.

As Brad Wilcox will tell you, marriage confers social, economic, and health benefits that are unlike any other affiliation or institution, and that’s even if you don’t land an HBS husband like Christie did! Getting married for the blood pressure perks would obviously be psychopathic, but in all likelihood, there very likely is something in it for you.

By contrast, artists know that there most likely isn’t anything in it for them. Matt Damon said the most helpful advice he got as a young actor was “It’s a terrible idea, don’t do it.” He thinks if anyone can dissuade you that easily, you will never make it in an industry as cutthroat and competitive as showbiz. You have to be willing to work for years without any glimmer of hope.

He always talks about he’d been in the SAG union for ten years, but after Good Will Hunting came out, suddenly he and Affleck were “overnight successes.” In truth, they wrote the movie out of desperation. They were so frustrated with their lack of opportunities (both had been passed over for Dead Poets Society, Primal Fear, and other plum jobs) that they essentially wrote the roles they wanted to have and then demanded the studios cast them as the leads.

Then, like most breakthrough successes, they had to deal with the confusion of fame and praise after years of toiling in obscurity. In Affleck and Damon’s case, they thought they’d be rich for life after they sold the script for Good Will Hunting, but after 6 months of renting a Hollywood party house, they were broke. Things turned out alright for them, but they show how success never turns out to be a sustainable motivation.

The ones who make it over the long haul come back to doing the work, the craft, the things that got them into it in the first place. While our relationships will likely never be covered by People, there are obviously pitfalls where a healthy relationship can sour, and there is a corollary to honing the craft rather than chasing good feelings or external approval.

In an age when so much envy-inducing relationship content is packaged for public consumption, it’s worth aiming for a marriage that won’t compute (to paraphrase Wendell Berry). Stockpile references that are incomprehensible to outsiders, inside jokes that are teeth-grating for onlookers, and then don’t worry when you forget where they came from in the first place. Treasure those moments of vulnerability that are ineffable, that can only be shared between the two of you, and then don’t tell anyone about it. Ask and give forgiveness for the most embarrassing faults, and then choose to continue loving each other anyway.

Those are the little moments that turn out to be the best parts.

The rest is just icing on the cake.

“In an age when so much envy-inducing relationship content is packaged for public consumption, it’s worth aiming for a marriage that won’t compute (to paraphrase Wendell Berry). Stockpile references that are incomprehensible to outsiders, inside jokes that are teeth-grating for onlookers, and then don’t worry when you forget where they came from in the first place.” I really loved this essay. Thanks for the shoutout, too.

What a moving piece. The analogy to addict behavior—! Happy to have read this as a young woman prior to marriage; I'm tucking it away for future reference.