Fight Club, Mark Driscoll, and the Young Men Returning to Church

On the 25th anniversary of Fight Club...

Short note: This piece is a bit longer than usual, so if you’re reading in email, you may need to click on the title to read the whole thing.

There are a bunch of clips from Fight Club and Mark Driscoll that I included. I’ve linked to timestamped videos for all of them, but the relevant portion is included below the video if you just want to read on.

NB: some clips have salty language.

Without further ado, here’s the essay…

When Rob McElhenney, who plays Mac on It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, was trying to get in shape, he went to the famous Hollywood trainer Arin Babaian. McElhenney said, “I have an ideal male body that I want to go for.” Babaian replied, “Don’t tell me what it is. Every dude for the last twenty years that wants to get in shape says the same thing: ‘I have the ideal male body that I’m trying to achieve.’ And I already know what it is. Brad Pitt, Fight Club.”

Fight Club hit theaters 25 years ago, today, and it’s a validation of its enduring relevance that Brad Pitt’s Tyler Durden is still, at least in some way, the masculine ideal. Of course, that’s the conceit in the movie as well. The narrator, played by Edward Norton, is a consumeristic, repressed, office drone, and he conjures up this alter ego, Tyler Durden, who stands for everything that he wishes he could be.

Here’s how the director, David Fincher, put the film’s premise in a 1999 interview: “It is talking about very simple concepts. We're designed to be hunters and we're in a society of shopping. There's nothing to kill anymore, there's nothing to fight, nothing to overcome, nothing to explore. In that societal emasculation this everyman is created.”

This everyman, the nameless narrator played by Edward Norton, learns halfway through the movie that he and Tyler Durden—the renegade, carefree, charismatic character played by Brad Pitt—are in fact the same person. Here’s how Durden explains his genesis in the narrator’s mind:

You were looking for a way to change your life.

You could not do this on your own.

All the ways you wish you could be, that's me.

I look like you wanna look,

I f— like you wanna f—.

I am smart, capable and, most importantly,

I'm free in all the ways that you are not.

On first viewing (and I might add, if you first watched the movie in high school), you can get lost in the vulgarity, violence, and absurdity of it all, and merely enjoy the big twist that Tyler Durden isn’t real.

But on second viewing, and as we look back 25 years later, it’s worth considering why Pitt’s look and performance remain so iconic.

Fight Club has proved prescient, and if you rewatch those scenes where Tyler Durden is critiquing the modern emasculated man, they remain just as relevant for subsequent generations of men as they were for Gen X at the time.

Let me give you a few examples.

If you’ve seen the movie, you’ll recall that after the narrator and Durden meet briefly on a plane, the narrator’s apartment is destroyed in an explosion. Disoriented, he calls Durden, and they meet at a bar.

Listen to this conversation again, keeping in mind that it’s between the narrator as he is, played by Norton, and as he wishes he could be, played by Pitt.

When you buy furniture, you tell yourself, that's it. That's the last sofa I'm gonna need. Whatever else happens, I’ve got that sofa problem handled.

I had it all. I had a stereo that was very decent. A wardrobe that was getting very respectable. I was close to being complete.

After awhile of this, Pitt asks him:

Do you know what a duvet is?

Norton: A comforter.

Pitt: It's a blanket. Just a blanket. Why do guys like you and I know what a duvet is? Is this essential to our survival in the hunter-gatherer sense of the word?

No.

What are we, then?

Norton: I dunno. Consumers.

Pitt: Right. We're consumers. We are by-products of a lifestyle obsession.

Murder, crime, poverty: these things don't concern me. What concerns me are celebrity magazines, television with 500 channels, some guy's name on my underwear.

Rogaine. Viagra. Olestra.

Then they go out behind the bar, and that’s when Durden asks for a favor: “I want you to hit me as hard as you can.” They end up fighting in the parking lot, marking the beginning of the narrator’s transition from mild- mannered employee to fight club ringleader.

In many ways, Durden is the embodiment of the Nietzschean ubermensch— rejecting passivity, weakness, and comfort—tearing down the old order first through fight club and then through his paramilitary group “Project Mayhem.” He’s powerful in an archetypically masculine sense, and perhaps it’s no accident that a few years later, Brad Pitt would play Achilles in the movie Troy. Durden and Achilles both represent a certain kind of manliness that Pitt embodied.

A lot of the scenes that were satirical in 1999 are now just reality in 2024. There’s the infamous placement of Starbucks cups throughout the film, but Starbucks is 30 times bigger today than it was then. The portrayal of office culture isn’t off-the-mark; it’s just banal after The Office, Workaholics, and the rise of BS, email jobs. If a penchant for Ikea catalogs was the narrator’s biggest flaw, I shudder to think how contemporary man’s comforts could be skewered.

Even that scene where the boss finds the rules for fight club left on the xerox machine and Norton’s character threatens him feels a bit on-the-nose today:

Well, I gotta tell you, I'd be very, very careful who you talk to about that. Because the person who wrote that is dangerous. And this button-down, Oxford-cloth psycho might just snap and then stalk from office to office with an Armalite AR-10 carbine gas-powered semiautomatic weapon, pumping round after round into colleagues and co-workers. This might be someone you've known for years. Someone very, very close to you.

David Fincher said that line got huge laughs in initial test screenings. Then Columbine happened, and suddenly, it wasn’t funny anymore. Now, disaffected males going on shooting sprees is a regular occurrence.

The famous “Middle Children of History” speech still connects:

I see in Fight Club the strongest and smartest men who've ever lived. I see all this potential. And I see it squandered. Godd— it, an entire generation pumping gas. Waiting tables. Slaves with white collars. Advertising has us chasing cars and clothes. Working jobs we hate so we can buy s— we don't need.

We're the middle children of history. No purpose or place. We have no Great War. No Great Depression. Our great war is a spiritual war. Our great depression is our lives. We've all been raised on television to believe that one day we'd all be millionaires and movie gods and rock stars. But we won't. We're slowly learning that fact. And we're very, very pissed off.

It’s a spiritual crisis, but one where traditional religion or Christianity is clearly not the answer. As Durden says at one point, “You have to consider the possibility that God does not like you. He never wanted you. In all probability, He hates you. This is not the worst thing that can happen. We don't need Him!”

In this sense, Tyler affirms that God is dead and rejects the slave morality of Christianity, the feminizing effect of religion, and even women altogether as anything more than toys. Instead, Durden pushes the narrator to connect with his primal side. They fight, they sleep on a ratty mattress in a ramshackle house, they have no TV.

And after a month, the narrator doesn’t miss his old life, and after fighting, the rest of his existence feels easy, even dull.

In self-discipline, he has found freedom, in fight club he has found purpose.

But it doesn’t last.

The narrator gets jealous that “Tyler” seems fond of a bright-eyed newbie nicknamed “Angel Face” (played by Jared Leto), so the narrator pummels Angel Face so brutally that the censors in England demanded Fincher shorten the scene. It made them too uncomfortable. To Fincher, that meant mission accomplished: it’s supposed to make you feel uncomfortable, to show that fight club wasn’t the answer. When the narrator gets up, all he can say for himself is, “I felt like destroying something beautiful.”

Which raises the question of how “right” Tyler Durden was, how complete his solution to modern emasculation was.

In the final scene of the movie, the narrator finally confronts Durden, trying to get him out of his head. Durden explains, “You need me. You created me. I didn't create some loser alter ego to make myself feel better.”

Then the narrator shoots himself in the mouth, and Tyler Durden falls to the ground dead. In some way, symbolically, the narrator has integrated what Durden represented, killing off the crutch of his schizophrenic alter ego.

Then his love interest, Marla Singer, comes in, and if you listen closely, as he tries to talk with a bullet hole in his cheek, his speech goes from all garbled to crystal clear as he tells her, “Trust me. Everything's gonna be fine. You met me at a very strange time in my life.”

Then all the buildings Tyler had rigged explode and the credits roll, leaving it unclear how exactly the narrator will live moving forward, to what extent he will be like Tyler Durden.

Likewise, men may viscerally connect with Fight Club and admire Brad Pitt’s physique and charisma, but where do they go from there? Starting their own fight clubs isn’t a complete answer (though many people did that in response). If Fight Club remains the definitive portrayal of masculinity and its discontents in the 21st century, what’s the answer?

One characteristic response in the Christian West came from Mark Driscoll.

About the same time as Fight Club came out, he was looking to create a hyper-masculine, punk-rock brand of Christianity in Seattle. He self-consciously styled himself after Fight Club. Here’s a rant on consumerism and masculinity where he even picks up on Durden’s line about “some guy’s name on your underwear” [timestamped clip from The Rise and Fall of Mars of Hill podcast]:

You don’t know what it means to be a man so you let marketing and advertising define masculinity, and you think if you buy the right things then you’re a man. And it’s all about consuming, as if being a man was defined by how much meat you can shove through your colon, and how many beers you can pound, and how fast you can drive, and how stinky you can fart, and how far you can spit, and how loud you can belch, and whose name’s on your underwear, and how big the mud flaps are on your truck.

He even had an extreme, pseudonymous (and now infamous) online persona named William Wallace II, who presented the exaggerated, crude, brash version of what Driscoll preached. But much like Durden, over time, Driscoll slowly became more and more like this hyper-masculine stereotype of himself. Eventually, he dispensed with the pseudonym but not the rhetoric.

As he wrote in his 2006 book Confessions of a Reformission Rev, he needed to adopt this persona to combat the “emerging-church-type feminists and liberals.” He eventually called a meeting with the men of the church where he handed them all rocks (to symbolically give them their “stones” back) and then yelled at them about how they needed to stop sleeping with their girlfriends and watching porn because “you can’t charge hell with your pants around your ankles, a bottle of lotion in one hand, and a Kleenex in the other.”

In some ways, Driscoll’s appeal (and ultimate demise) was the same as Tyler Durden’s. Both saw modern men and Christianity as effeminate. While Durden was focused more on consumerism and “slaves with white collars,” Driscoll’s chief enemy was the progressive city of Seattle and emasculated men who were irresponsible and undisciplined.

He called on the men of the church to wage a culture war. Behind the progressive enemy’s lines, they would marry young, get good jobs, raise large families, and essentially colonize Seattle through population dominance.

He used military imagery—calling men’s weekends not “retreats,” (because real men don’t retreat), instead calling them men’s “advances.” The ministries were Air War and Ground War. Men who failed to achieve his vision of manhood were called colorful names. To give one example, “Artistesticularless” referred to “men who expect women to take care of them because they play guitar or paint.”

If Tyler Durden elevated physical aggression, Driscoll showcased rhetorical aggression, falling somewhere between an insult comic and a drill sergeant:

Here’s Driscoll’s recollection of a Promise Keepers rally he attended in the 90s, a group he often used as a foil for his own masculine vision [with timestamped clip]:

And I thought, well, great, men’s meeting, in a football stadium. This will work. And I get there, and the first thing I see is all the leaders are wearing pastel colors, and the guys are up on the stage singing love songs to Jesus. And next thing I know, a guy kind of preaches, and all of a sudden I’ve got a bunch of guys I’ve never met, crying and hugging me. I was like, “What in the world is this?” I’ve been to football games here and they don’t do this at halftime.

Or here’s his bit on immature men [with timestamped clip]:

You want a guy you can marry and have babies with. You don’t want to marry a guy who’s a baby. This is unbelievable. I swear to you, I keep waiting to go to the mall and just I’m waiting for the day when guys are in strollers. Just with meat binkies and sippy cups full of beer. And the girlfriends are like, “Oh, he’s nice, he’s got potential. I think he’s got a lot of potential.” “Oh, I messied, I messied.” It’s like, Good Lord.

Like Tyler Durden, Driscoll is clearly flawed and left a trail of wreckage behind him, but you can see why he was so popular. He’s a gifted speaker, and his critiques (if not his solutions) have some merit. Juxtaposed with his hand-wringing critics, he has a vitality and confidence.

Like Durden, he built a movement around his personality and singular vision of the world. He tapped into modern man’s aimlessness, just like in Fight Club, and his answer boiled down to male dominance and his own machismo, essentially attempting to merge the Nietzchean ubermensch with the Christian concept of male headship.

But just like Fight Club, his solution proved unsustainable, and when he failed, so did the church.

Yet, the underlying problems that Fight Club and Mark Driscoll were tapping into still remain.

Young men are floundering.

So the question is: if Fight Club laid out the problem, what’s the answer?

In 1999, the same year Fight Club came out, Lee Podles, a Catholic writer and the Senior Editor of Touchstone Magazine, wrote a book titled The Church Impotent: The Feminization of Christianity. This seminal book made the case that Western Christianity had become, at a theological and cultural level, more attractive to women than men. Due to its emphasis on a passive reception of divine activity, devotion that strayed into romantic and sentimental territory, and its perceived glorification of weakness and femininity, even among denominations with all-male leadership, the pews and committees were predominantly populated by women.

Podles’ definition of masculinity is slightly more nuanced than the common active/passive distinction. He argues that the masculine pattern is initial union (with the mother), separation, and reunion, while the feminine pattern is a maintenance of unity. Because boys are a different sex than their mothers, there is a necessary phase of separation and testing before they can return to society and the feminine to offer their strength and sacrifice. This is the hero’s journey.

Although, he argues, that initial separation leads men to always be wary of an overly feminizing influence or anything that could risk their masculinity in the eyes of their peers. Hence, their flight from churches or occupations they see as feminine. To use a classical example, he points to the threat Calypso poses to Odysseus’s manhood, the temptation to “withdraw from the struggle to establish male identity into the safety of the feminine, into a puerile cocoon of pleasure and safety.”

By contrast, war is the quintessential masculine activity. Men must leave the comforts of the feminine, face death and difficulty, and through that transformation, they can return to society and have something valuable to offer.

Thus we see men coalesce around, if not war, war-like activities: football, boy scouts, fraternities. Pain, challenge, duty, self-discipline—these sacrifices intuitively appeal to men.

Driscoll loved to contrast popular Christian sentimentality with his own vision of Jesus as a fighter and warrior. Here’s him preaching on a passage in Revelation [timestamped clip]:

Then I saw heaven open. Boom! There’s Jesus. He gets a snapshot, the curtain is pulled back. And behold, a white horse. I love this. How many of you grew up watching Westerns? The good guy always rides the white horse. It’s biblical! The one sitting on it is faithful and true and in righteousness, he judges and makes war. You know, Jesus will never take a beating again. That was a one-shot deal for salvation, that is not an ongoing job for Jesus, to take a beating. “His eyes are like a flame of fire.” I just love this. This is Ultimate Fighter Christ. A hip hop buddy of mine calls it “thug Jesus.”

But we’ve been trending away from “thug Jesus” in the West for some time. Podles traces the feminization of Christianity back to the high middle ages and the rise of Bridal Mysticism, which encouraged Christians to envision themselves individually as the “bride of Christ,” a sort of foreshadowing of the much-mocked “Jesus is my boyfriend” worship songs of today. He also points to the concurrent rise of Scholasticism, which separated academic theology from spiritual practice.

This set the stage for today, where professors of theology and religion may be agnostic or atheist while church attendance and devotion is seen as a female pursuit that husbands are often dragged to or men opt out of entirely. In short, many men have agreed with Nietzsche’s assessment: you can be a man or a Christian but not both.

That’s why there’s been much ado these past weeks about young men returning to church. Jordan Peterson and Russell Brand recently led a crowd of 25,000 in The Lord’s Prayer at their “Rescue the Republic” rally.

And a much-discussed New York Times piece reported that young men are returning to church and approaching parity in the pews with young women. The primary explanation offered is that Christianity is now coded right-wing, traditionalist, and patriarchal. The growing polarization of the sexes means left-leaning women opt for more progressive or non-Christian spiritual expression while men seek community and structure in Christian churches where they are not viewed as inherent oppressors.

In some ways, this is a continuation of Driscoll’s thinking. There’s a culture war going on, men are under attack, and the Church needs to be a place where men can be men. It’s an understandable impulse, but the risk is that a church built on opposition to wokeness or feminism or some external cultural ill is not stable.

Mainline denominations swelled in the Cold War years because they were patriotic, Christian symbols in contrast to the atheistic Soviet Union. But when that opposing force went away, the parishioners did too.

So while a war against wokeness may get male butts in chairs for a time, it’s worth casting a wider gaze.

There is one Christian group that had gender parity, even a male majority, back in 1999 when Podles wrote his book. And it’s only risen in cultural relevance since then. That church is not making a pitch on being right-coded, but it’s seen young men come into it steadily over the past 25 years.

That church is the Eastern Orthodox Church.

To be clear, Orthodoxy isn’t the only place you’ll find Christian men, and Podles himself doesn’t dwell on the Eastern church in his book. But it’s worth taking a moment to consider the relevant, unconventional answer the men of Orthodoxy present to Nietzsche, Durden, and Driscoll’s critiques of Christian masculinity.

“Why are men drawn to the Orthodox Church?” Some years ago, the Orthodox theologian Frederica Mathewes-Green was asked this question, and she realized it’d be simpler to just ask them, so she reached out to her male friends and compiled their explanations. If you listen to the testimonies of the men who joined the Church, you will hear echoes of this masculine desire for difficulty, for a noble conflict, and for sacrifice finding a healthier outlet.

One man simply said, “Orthodoxy is serious, it is difficult, it is demanding.” And you can sense that the moment you step into a service, even if you can’t put your finger on it. The way the Catholic writer Patrick Arnold put it is that, “liturgy that appeals to men possesses a quality the Hebrews called kabod (‘glory’) and the Romans gravitas (‘gravity’); both words at root mean ‘weightiness’ and connote a sense of dignified importance and seriousness.”

The Divine Liturgy has gravitas.

Recall one of the first things the narrator experiences after moving in with Tyler: he sleeps on a crummy mattress, without a TV or any of his cozy furnishings. After a month, he no longer misses any of it. Asceticism is foregrounded in his quest to break free, but it’s portrayed as a means to strength not a shameful penance.

Podles makes the point that in the West, the idea of fasting is often more penitential, while in the East, it’s treated as a method of spiritual purification and strengthening. He argues Western culture has become a culture of guilt and innocence, but it used to be a shame and honor culture. Christianity’s first millennium was focused on honor and the crown of righteousness, achieved through martyrdom or monasticism. The Desert Fathers did battle with the Devil.

While this idea remains in the East, over time in the West, Christianity became focused on satisfying the Father’s honor, anger, or judgment, making innocence and guilt the dominant paradigm. The chief antagonist of the story slowly shifted from death, the Devil, and the demons to, effectively, God the Father, who must be assuaged—or simply nothing at all. We just must love ourselves.

To return to the idea of sleeping rough, while it may sound funny, it’s not uncommon to hear of Orthodox men not owning a bed, TV, or other amenity for spiritual reasons. That’s in addition to regular fasts from meat and dairy, periodic fasts from marital relations, and dry fasts before receiving communion.

Men will go to great lengths to achieve physical fitness. The asceticism at the heart of Orthodoxy, its physical difficulty, appeals to man’s desire for freedom through self-discipline.

There is martial imagery employed in Orthodoxy, but it isn’t bombastic, goofy, or forced, like Mark Driscoll’s “men’s advances.”

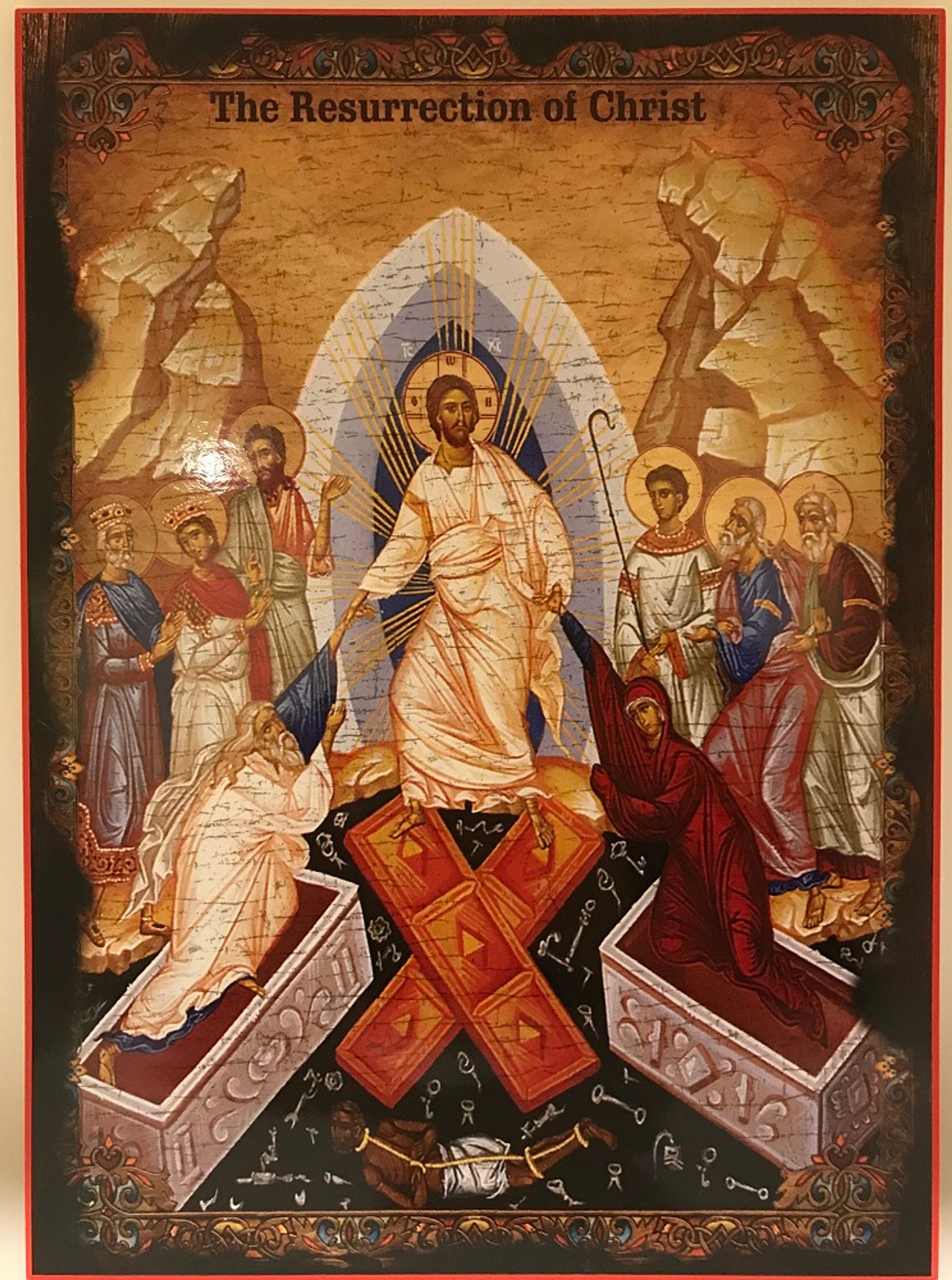

The Warrior Jesus (and Warrior Virgin Mary, for that matter) are present, but in Orthodoxy, the emphasis of salvation and the cross is Christ’s triumph, and the gospel is an invitation to join Christ in the fight against evil. This gives men an active, noble conflict to dedicate themselves to, one not built on cultural antagonism or pastoral magnetism. The war is against their own passions, weakness, and, yes, demons.

There is not a liberal bogeyman, nor an attempt to be relevant and cater to you. It is reality, and it is demanding something of you. And young men often respond to that.

Here’s a convert priest explaining how men are drawn to the dangerous element of Orthodoxy, which involves:

The self-denial of a warrior, the terrifying risk of loving one's enemies, the unknown frontiers to which a commitment to humility might call us. Lose any one of those dangerous qualities, and we become the Joann Fabric Store of churches. Nice colors and a very subdued clientele.

Men get pretty cynical when they sense someone's attempting to manipulate their emotions, especially when it's in the name of religion. They appreciate the objectivity of orthodox worship. It's not aimed at prompting religious feelings but at performing an objective duty.

This idea of gratitude for objective duties was a common sentiment. Men were grateful to have straightforward guidelines rather than an emphasis on spontaneity or emotional experiences. Men don’t like looking stupid. They also appreciate a destination.

In Orthodoxy, that involves the concept of the nous, a Greek word which Mathewes-Green defines as the “receptive” mind, “the understanding or the comprehension rather than the cogitator that's always constructing things. The nous is the aspect of the mind that can understand, and it's designed to perceive the voice of God.” The spiritual disciplines of Orthodoxy help purify us of distractions and sins that inhibit the nous and thus our apprehension of God.

Once this concept is in place—a real, challenging goal for men to strive for—the Christian life changes. One man said: “Noetic reality had become completely distorted in the Christianity that I knew. Either it was subsumed into the harsh rigidity of legalism, or it was confused with emotions and sentimentality, or diluted by religious concepts being used in a vacuous, platitudinous way. All three of these: uptight legalism, effusive sentimentality, and vapid empty talk are repugnant to men.”

A deacon wrote: “Evangelical churches call men to be passive and nice. Think Mr. Rogers.

Orthodox churches call men to be courageous and act. Think Braveheart. Men love adventure, and our faith is a great story in which men find a role that gives meaning to their ordinary existence.”

But unlike Driscoll and Durden, who leaned into men’s power to the point of domination and disordered masculinity, Orthodoxy is more subtle.

One priest emphasized that in our culture, we often have two stereotypes of men, “Be strong, rude, crude, macho, and probably abusive. Or be sensitive, kind, repressed, and wimpy. But in Orthodoxy, masculine is held together with feminine.”

To that point, one respondent noted that there was “something much prized among the saints, which was the baptism of tears, a spiritual gift of tranquil deep repentance and compassion, expressed in gentle and in sometimes continuous tears.”

In Orthodoxy, tears of repentance and masculinity aren’t a contradiction.

Another priest said: “It's an illusion that men and women have, ‘different spiritual needs’ mandated by gender, because each person relates to Christ directly from the deepest interior person. Those sorts of categories of spirituality specialization are unhelpful except as a marketing tool.”

At root, men are called to be like Christ, but in the East, as Frederica Mathewes-Green emphasizes in her book Two Views of the Cross, Christ’s crucifixion is presented as a triumph over death, a view known in the West as Christus Victor.

She uses an analogy of a police officer rescuing hostages. If the officer was captured, tortured, and killed in the process, and we made a statue to honor him, how should we depict him? In the East, images of the crucifixion aren’t gory. They are triumphant. The hymnography speaks of how:

Death seized Thee, O Jesus,

And was strangled in Thy trap.

His gates were smashed, the fallen were set free,

And carried from beneath the earth on high.

And

Thou hast destroyed the palaces of hell by Thy Burial, O Christ.

Thou hast trampled death down by thy death, O Lord,

And redeemed earth’s children from corruption.

You can hear hints of this view in Driscoll’s references to “fighter Jesus” or “thug Jesus.” He instinctively rebels against a type of Christianity that had lost this traditional view of salvation and the Christian life, but he lacks sophistication and offers crude, in all senses of the word, solutions.

Which brings us back to Fight Club, and the men returning to church today. What Fincher said back in 1999 still obtains: “There's nothing to kill anymore, there's nothing to fight, nothing to overcome, nothing to explore.” But if Christianity is reduced to a red-pill religion for spiritual-warfare-as-civilizational-warfare, its growth will prove to be a Pyrrhic victory.

But there is something going on, some ominous portents.

As Mary Harrington put it in a recent column, it seems that both metaphorical and literal demons are emerging, whether it’s Elon Musk warning that with AI we’re “summoning the demon” or actual, explicit occult practice breaking into the open. The secular materialist consensus is breaking down, and the old gods are returning.

She warns, if things get any stranger, “one thing is sure: wooly inclusivity and a limp handshake won’t be enough. We will all need the Armour of God.”

In other words, we will need Christian Men.

Fascinating piece. Thank you for sharing it. As an evangelical who got wrapped into the Driscoll thing as an 18/19 year old, and has now seen through the faults in it, I liked much of your analysis. I’d also say, evangelicalism at its worst is as you describe it. But reading someone like John Stott or to go back further—John Owen, Charles Spurgeon or John Bunyan—brings more nuance than a Driscoll (or his ilk). There is imagery of Pilgrimage, multiple pictures of atonement including Christus Victor, and examples of men who did not choose a culture war version of Christianity, but a robust, Christ-centric vision of men (and women) on a dangerous journey to glory, with the Spirit’s help indwelling and empowering those steps.

I see I’m a bit late to the party on this piece but bravo! It’s a nuanced appraisal of the trend of been seeing.

As an Anglican priest I can venture- many Anglicans I know are starting to see Orthodoxy as a more natural partner with/end of our theological aims than Roman Catholicism.

I think the main difference between us is in what degree of security can be found in the “certainty” of Church history (and how much cartoonizing of CH is required to get the prize of absolute assurance/ and how “evangelical” is that tendency anyway- people like David Bentley Hart suggesting it’s a Protestant hold over being imported to Orthodoxy via conversions may have a point). In the end, that’s what I take your “red pilled spiritual warfare as cultural warfare” comment to allude to. I wager that’s the internal fight western Orthodoxy will have on its hands for the rest of this generation. I’m praying hard that the right sides prevail!