A Life of "Whim"

Rather than Shame and Self-flagellation

The other day, I came across a photo of a beautiful celebrity, posing in a field with her husband and three dogs. I hadn’t been expecting it (I use X just for news), and I felt an immediate flush of envy at her picturesque life.

Then, I thought, “How’d they get that photo?” I have 3 dogs too, and getting them all roughly in position requires treats, funny noises, and then rapidly posing. I can be almost certain that this seemingly perfect photo—the one that’s making me feel bad about myself—was actually complete chaos to produce.

Okay, so what? Hardly worth mentioning that social media invites comparison, often unfavorable.

But as I thought more about how dogs never pose easily for photos, I couldn’t stop thinking, “How much of a hit does their real relationship take in the process of presenting it as perfect?”

Mary Harrington argues that our attention economy tempts us always to chase “clout,” which she defines on the internet as “the number of eyeballs you can persuade to notice you online…Building up clout can be done several ways, but perhaps the two most common are emotional exhibitionism and identity-politics controversy.”

She expanded on how clout-chasing can take over our lives:

For the digital domain, left unchecked, seeks to extend the logic of the market ever further into the human heart, by enclosing and productising emotion and relationship. A sense of access to other people’s intimate lives is what keeps people clicking; so the machine lavishly rewards every gobbet of intimacy you are willing to feed into it. And while [popular influencers] Mother Pukka and Alison Johnson both seem some way from total self-productisation, a professional profile that relies on intimate photos and videos makes self-disclosure central to both their products. Pictures of the kids; footage in bed or half-dressed or kissing the boyfriend; sometimes wrenchingly personal accounts of fear, uncertainty, or stress. Once such material is a source of income and professional clout, the disclosures have to keep coming: the machine always wants more.

And this is the two-edged sword. In the smartphone age it’s difficult enough, as a parent, to avoid the temptation to stop colouring or pumpkin-carving or whatever with your kid and take a photo of what you’re doing for the grandparents. So what happens when it’s not just grandparents, but an audience of thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands? What is it like to have a marital argument, in full knowledge that your heartfelt feelings might form the basis of your spouse’s viral post the following day? What would it be like, as a child, to do pumpkin carving with Mummy, while intuiting at some level that you’re not just making memories but also sponcon [sponsored content]? Is it even possible to have intimate relationships, when the all-pervasive incentive at every moment is to expose intimate details of those relationships for clicks?

As an antidote, she proposes “digital modesty,” which includes principles for posting such as:

no pictures of my child or husband

no selfies

no discussion of any of my interpersonal relationships except with the other party’s explicit consent

pictures of friends only in a professional context

self-disclosure only in the context of wider argument

Without “digital modesty,”

There is no intimate domain that can’t become sponcon; no relationship that can’t be strip-mined for clout. And relationships thus mined are quickly exhausted. An economy of total exposure would be one of total alienation.

Strip-mining is the perfect analogy. In a world where everyone carries a camera connected to the internet, the temptation to mine your life (or worse, your kid’s life) for content can be intense. And it can seem innocuous enough to, as she says, stop carving the pumpkin to take a photo for grammy, but stories like mommy influencer Jordan Cheyenne urging her son to cry for a video thumbnail should be warnings to us all of how slippery the slope can be.

I’d like to draw a seemingly unrelated connection between social media and reading. As Harrington says, the smartphone era tempts us to chase clout through strip-mining our own lives. We take good things—our fitness, our relationships, our trips—and commodify them, treating them as a means to an end, an instrumental good.

Long before the smartphone era, reading was freighted with external expectations, comparisons, and obligations. People felt and still feel pressure to read more, read “better books,” and to be seen as a “reader.” They want to cross things off, to have read books, to sound smart at dinner parties. This sucks the joy out of reading, much like posting sucks the joy out of the moment.

Alan Jacobs’ wonderful book The Pleasures of Reading in an Age of Distraction offers an approach that applies across all of life in our instrumentalized, smartphone era: follow “Whim.”

As a philosophy of reading, “Whim” encourages readers to “Read what gives you delight—at least most of the time—and do so without shame.” At another point, he reiterates, “It should be normal for us to read what we want to read, to read what we truly enjoy reading.” This is meant to offer an alternative to the common motivations for reading that center on obligation and shame.

Obligation leads to reading as “strip-mining” (a phrase Jacobs uses just like Harrington). Reading as strip-mining demands we skim websites and hyperlinks, listen to all audiobooks at 2x, and prefer book summaries to books. (In SBF’s immortal words, “If you wrote a book, you [messed] up, and it should have been a six-paragraph blog post.”) AI seems to promise the pinnacle of this sort of impersonal information condensation.

This type of reading may be well-suited to news articles or cookbooks, but Jacobs says that to strip-mine Stephen King, Song of Solomon, or Homer would miss the point and the pleasure of the whole thing.

Of course, reading can be joyless not because it’s too businesslike but because people are ashamed that they’re too lowbrow. When literary critic Harold Bloom was asked about Harry Potter’s enormous success, he replied, “I know of no larger indictment of the world’s descent into subliteracy.”

Jacobs says that this approach turns reading into “eating your broccoli”—“some assiduous and taxing exercise that allows you to look back on your conquest of Middlemarch with grim satisfaction.” C.S. Lewis called this reading as “social and ethical hygiene.”

As Jacobs put it in an interview (that’s well worth the listen): “Don’t go around making your reading life a kind of means of authenticating yourself as a serious person. It’s just no way to live.”

Jacobs makes two key points:

By reading what you genuinely enjoy, you may well end up “upstream” of that original book. You love The Lord of the Rings, so you read what influenced Tolkien, and you end up at a classic like Beowulf but minus the shame and obligation. You’re led by Whim, and while this is less formal, there is an “emergent structure” built around what nourishes your spirit and piques your interest.

There is a season for everything. There may be times where you are hungry for a challenge and thus choose a book that you know will be beyond you. Conversely, there may be a time when you really just want to read crime novels for a year. It’s better to allow for both than to force yourself to read what you feel you “ought.” You don’t read Great Books every day just like you don’t have a 7-course French dinner every night. Your spirit must align with the demands of the moment.

Since we all now live in a sea of content and choice, Jacobs’ book only becomes more relevant with each passing year. That doesn’t lessen the public’s demand for direction. Ted Gioia just published a 12 month guide to an education in the Humanities in response to reader requests.

His guide gives a helpful place to start, and I don’t doubt that people genuinely desire it. But there are also plenty of people—from Milton to Bloom—who have written such guides already.

Not to say that Gioia isn’t a wonderful thinker or writer, but I stand with Jacobs that most of us don’t need that much more information or guidance on what “The Canon” is. We think we need a reading program like we think we need a new diet. In reality, we already know the basics of what we “should” read and “should” eat. What we lack is sufficient motivation to commit to such a strict routine.

Re-read Gioia’s description of how he became well-read, and he likens it to training for the Olympics. His approach:

I IDENTIFY GAPS IN MY READING EDUCATION, MAKE LISTS OF BOOKS I NEED TO READ TO FILL THE GAPS—THEN I READ EVERY BOOK ON THE LIST

The first time I did this was around the time I graduated from Stanford Business School. I had now completed my formal education, but there were still huge gaps in my learning—so many essential books that I still hadn’t read.

So one day, I sat down and made a list of the 50 most important books that I still hadn’t read. During the subsequent months, I read every book on that list.

Does this sound like you? Does this sound like anyone you know?

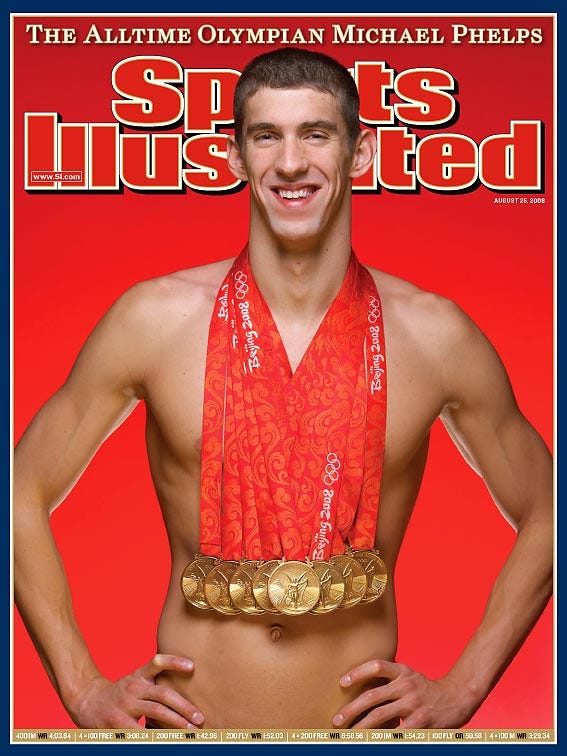

Some readers, like Gioia, are clearly able to read in this way. Also, Michael Phelps trained for 30-40 hours a week for 5-6 years before the 2008 Beijing Olympics, but does that sound like you? Does that sound like anyone you know?

No one would tell a couch potato to attempt Phelps’ regimen. How reasonable is it to attempt Gioia’s for any but the most obsessive reader? Moreover, would you want to generalize this approach? Make lists of cities, restaurants, and experiences you want and then just plow through it all?

Both “digital modesty” and reading at “Whim” share a fear of instrumentalizing—and thus souring and hollowing out—life. This desire to be “efficient” and “maximize” our lives is deep-rooted and often uncritically accepted.

Hiking is fine, but hiking and posting a glam shot is better. Romantic dinner is fine, but romantic dinner plus adorable photo is better. Saying you’re reading is fine, saying you’re reading The Brothers Karamazov is better, and referencing “The Grand Inquisitor” scene as well may be best of all. It is reading to have read, living to have lived.

But there is a cost. The hike, the dinner, and the reading all become subservient to some other end, and in the process, they are cheapened.

Jacobs advocates “Whim” as a means to get in touch with yourself in an honest way. Reading for intrinsic reasons will reveal things you would never discover if you read out of obligation, avoided reading out of fear, or only consumed algorithmically recommended content. Removing external pressure and input allows for self-discovery, but we live in a time of frenetic activity and compulsive technological use that crowds out silence, reflection, and depth.

It’s hard to get in touch with what you want, with “Whim,” in such times.

We can easily get caught up in how our lives compare to our friends or celebrities we see online, but here again, Jacobs’ reading advice is applicable: “Don’t waste time and mental energy in comparing yourself to others, whether to your shame or gratification, since we are all wayfarers.” Flogging yourself or patting yourself on the back both distract from living by “Whim,” which is inherently idiosyncratic and incompatible with comparison.

We are all so busy nowadays, trying to eke every last efficiency out of life. The reading equivalent of this would be working through 1001 Books You Must Read Before You Die. But reading to “get through” books is often ineffective and almost certainly unpleasant. Jacobs says, “If you’re thinking in terms of getting through books, I will gently suggest, maybe you should reconsider your life choices. What are you chasing? What is it that’s flogging you?”

Rather than chasing novelty, efficiency, or authentication as a serious person through your reading, Jacobs praises rereading books. Indeed, rereading is one of the most “Whimmy” things you can do. It will not gain you clout nor a new book to cross off the list. Nevertheless, any good book is worthy of more than one pass, and reading with care will likely yield deeper insights and certainly be more pleasurable and motivating in the long run.

In the end, strip-mining is not a durable strategy for reading or living. It’s exhausting.

So I’ve thrown my lot in with “Whim,” knowing this will mean I read fewer of the books I’m supposed to but more of the books I love. I will have a life fewer envy but one I enjoy much more. I will preserve something precious but lose something fleeting. And I’m okay with that.

I enjoyed reading this, Ben. Reading Jacobs ' book a few years ago also inspired me to get into reading. The main reason I hadn't earlier was the very things you talk about - the bar being set too high over and over. It felt good to freely read at whim and as I have kept at it, I have been able to swim instead of flounder or sink in more complex "Great" works.