10 Reasons to Finish That Novel

(or sweater, or chair, or room...)

The Olympics just wrapped up, and I’m reminded once again of the gulf between normal people and elite athletes. I am young by most measures, but I am now entering the period where many competitors and pro athletes are my age or younger, and there is no escaping that the window for my childhood dream of making it to (either) the NBA or the NFL has closed.

Indeed, this feeling of mediocrity can easily spill over into the rest of your life. We are now globally connected, and you can compare your career, relationships, vacations, intelligence, etc. with literally the best of the best from around the world. The Olympic games of life are going on 24/7 on YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok, and none of us are making the podium.

While this competition may make us feel inadequate in our fitness or vacations, it can halt entirely our creative pursuits. If you were to putter around on a woodworking project, you might be embarrassingly bad. But you could instead watch a timelapse of hand-crafting a wooden canoe. You could try to learn chords, or you could watch a 4 year old virtuoso on the piano. You could write some jokes that aren’t that funny, or you could just watch a Netflix special of Ricky Gervais.

When you’re constantly reminded of how good the best in the world are, it’s hard to even try. Why risk looking foolish in a clumsy attempt? Much easier to leave it to the experts and enjoy the show.

The assumption embedded in this thinking is that to remain an amateur guitarist, surfer, or comedian would be time wasted. This approach treats creative projects like start-up investing. Sure, you may learn some things if the business fails, but at the end of the day, you’re in it for the shot at a 100x or even 1000x return. Boom or bust.

At the same time, you can watch the Olympics, see the heights of human achievement, and notice how many of exercise’s benefits accrue to amateurs. I can have a healthy body, enjoyable exercise regimen, and long life all without reaching the peak performance of an Olympian. In fact, I am at less risk for overtraining injuries and may well have a more functional body in the long run!

And I wonder whether exercise, not start-up investing, is really the better analogy for creativity—something where the 99%, not just the .001%, have much to gain.

Julia Cameron’s book The Artist’s Way is all about unblocking artists, but she defines art broadly. It may be dancing, pottery, or music, but it may be as simple as redecorating a room or tending a garden bed. The common thread is a creative impulse repressed. Perhaps you fear looking silly, or self-centered, or weird. But she argues that getting in touch with these creative impulses and integrating them can be life-giving.

I highly recommend The Artist’s Way as an oblique method to get in touch with your creative side, and I agree with Cameron that creativity is latent (but often partially blocked) within everyone. The benefits of creative expression are accessible to anyone, and here’s 10 things you can learn if you take on that novel, that room, or that class you’ve been avoiding (even if you’re never world-class):

Empathy

“If you’re going to stand up there by yourself and try and make me laugh, I love you, and I’m not going to criticize anything you do beyond that.”

The moment you try to write a joke, a short story, or a song, you go from cynic to creator. You become more generous and observant. You begin to wonder, “Now why did he put that shot in, why did she make that choice, why did he use that word?” You realize how hard it is to face a blank page, and you can get better at seeing what an artist was trying to do and appreciating the effort rather than smugly condemning the outcome.

Patience

“You just let this childlike part of you channel whatever voices and visions come through and onto the page. If one of the characters wants to say, "Well, so what, Mr. Poopy Pants?," you let her.” -Anne Lamott

One of Anne Lamott’s most famous pieces is a short one from Bird by Bird on first drafts. She describes the first draft as the “child’s draft, where you let it all pour out and then let it romp all over the place.” That’s the draft where dialogue might include “Mr. Poopy Pants.”

And you let all that happen because what you may well find is that “There may be something in the very last line of the very last paragraph on page six that you just love, that is so beautiful or wild that you now know what you're supposed to be writing about, more or less, or in what direction you might go -- but there was no way to get to this without first getting through the first five and a half pages.”

If, like me, you are prone to regret and beating yourself up for poor past decisions, you might find this idea liberating. It is unreasonable to expect in writing that your first draft will be your final draft, that it will be without missteps, backtracks, and reorientations. Why would you expect your life to be any different?

There isn’t just one way to do it.

There are certain creative myths that we latch on to. One is the moment of inspiration. And unless you’re a complete cynic that believes it is only peddled as PR and self-aggrandizement, there is a meaningful bloc of creatives who experience this. Paul Thomas Anderson wrote Magnolia in two weeks at William H. Macy’s cabin. Nic Pizzolato wrote True Detective in twenty-hour binges.

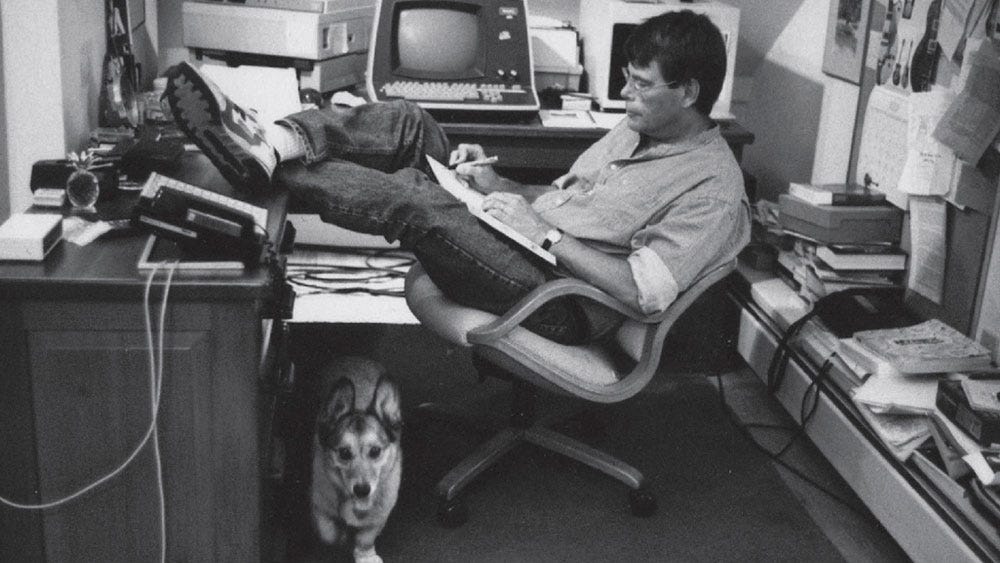

Conversely, there’s a much more plodding approach taken by no less impressive artists, perhaps most famously summed up in Chuck Close’s line, “Inspiration is for amateurs. The rest of us just show up and get to work.” Stephen King said, “Sometimes you have to go on when you don’t feel like it, and sometimes you’re doing good work when it feels like all you’re managing is to shovel s— from a sitting position.”

Some authors write with the end in mind, others are constantly surprised. Some outline, some don’t. Some edit as they go, some draft ugly and revise pretty.

You have to learn what works for you, not try to do someone else’s creative process, to live someone else’s life.

The value is in the thing itself

A common story is of artists honing their craft in obscurity, breaking through to popular success, finding fame unsatisfying, and slowly reconnecting with their craft.

There are too many examples of this phenomenon to count, and I’ve written about it previously, but one that’s stuck with me is Patrick Rothfuss’s description of his two book tours.

His first book The Name of the Wind became one of the most beloved fantasy books of all time, but when he went on that first book tour, it was only attended by a small group who caught on early. He signed a few autographs, chatted with some fans, and then got dinner with friends.

His second tour for The Wise Man’s Fear had a line around the block for every appearance, he signed books til his hand hurt, and then collapsed into his hotel bed in the wee hours of the morning.

He’s not sure which tour was better. And now, he can’t finish the trilogy and everyone hates him.

We’ve all but lost the distinction today between an honorarium and a wage, but there used to be an idea that certain leisure activities like writing couldn’t be compensated by a simple wage. An honorarium was a way of paying for a product while acknowledging that the value of the labor transcended and exceeded mere monetary terms.

Brings your attention down to human scale

It is easy to live in a state of distraction and hyperstimulation. This is compelling in the short run but exhausting in the long run. You can end up consuming more but retaining less, glutted but unsatisfied.

When you are working at a slower pace—whether it’s building a chair, reading a book, painting a canvas—you can really focus. It is restorative to bring some order out of the chaos and devote some sustained attention to a task rather than flitting from activity to activity.

Take a break from the services that hijack your limbic system, offer sustained focus to a challenging task, and you may find a little peace.

Undergirds your mind and self-esteem

This one is perhaps a little instrumental, but it’s too true to skip mentioning.

A meaningful hobby can make your mind feel fallow rather than untilled. A fallow field is left intentionally unplanted, while an untilled field is simply neglected. If you work on an essay for an hour in the morning, the ideas can simmer the rest of the day. Oftentimes, the phrase you were looking for or the resolution to a transition comes when you’re not at your desk.

Perhaps this is just my temperament, but I love this feeling of something working in the background. When the perfect line drops into my head unexpectedly, it’s delightful.

Additionally, a real commitment outside of work and home diversifies your life portfolio. A hard day at the office or with your family can be easier to bear if your morning at the studio went well, and vice versa.

Passively observing excellence does not feed your soul. Honing your craft does.

Learn to be process-oriented rather than outcome-oriented

One common trait among creators is dissatisfaction with their final output, even when it’s received with critical and popular acclaim. Here’s George Lucas:

I’ve got a pretty low opinion of my movies…[With most movies], you suffer through, and you think they’re terrible, and then people say, “Oh they’re great.” But it’s hard to get that [idea out of your head] that “they’re actually terrible” because I can see all the scotch tape and the rubber bands and everything holding it together.

And this is particularly true of Star Wars number 4…I was so disappointed about what my vision was and what it actually turned out to be.”

Creatives are driven by a desire to innovate, a desire to express themselves, perhaps just a desire to get something out of their head and onto the page. Regardless, they don’t hang their self-esteem or evaluation of a project on its reception.

This is the opposite of “do it for the gram,” of crafting your life in service of its presentation to others. Rather, it is living so that “even if you lose you win.” It is doing the right thing not for recognition, giving without expecting to receive, living in the moment.

Accept Limitations as a Gift

Robert Frost once compared free verse to “playing tennis without a net.” There’s a few ways to take that, but one is that a game without any rules or structure loses its meaning and value. Chess would not be fun without proscribed movements for the different pieces.

Artists will sometimes place strict limits to stimulate creativity. Jack White is a big proponent of this approach.

He would limit time in the studio. They made White Blood Cells in three days. They used three as a guiding limit: Red, white, black. Vocals, guitar, drums. Storytelling, rhythm, melody.

It can be easy to think, “If I moved to…”, “If I had more money…”, “If I worked at…”, if my situation or constraints changed, then I could have the thing I want.

It’s worth considering whether the community, romance, entertainment, or whatever it is, can be found in your current life with its current limitations.

Necessity is the mother of invention, and sometimes dreams of running away from your problems and starting over are just a siren song.

Makes you grateful to be human

One of the recurring themes of the early seasons of Black Mirror is gratefulness for the organic limitations of embodiment. One premise (which doesn’t feel too far off), is what if everyone had tiny cameras the size of contact lenses that allowed them to replay any moment from their life on-demand?

We watch as a couple’s relationship drifts into stagnation, jealousy, and ultimately rupture because they are literally unable to forgive and forget.

Modern life can make us into machines. Our phones and computers act as technological prosthetics (and sometimes crutches) for our brains. There is an influential lobby that presents the brain as inferior to computers in all sorts of ways (biased, irrational, temperamental, etc.). We can struggle to focus on routinized tasks, tasks where our humanity (with its sense of boredom or desire to not stare at spreadsheets for 8 hours a day), becomes a liability.

Art can help you appreciate your humanity a bit more.

Art makes you more alive

When you are looking for a new car, say a Honda Accord, suddenly you begin to see it everywhere. Your perception is shaped by your interests and your knowledge.

Creating can bring wonder and delight at the simplest of things—a brilliant turn of phrase, a flower in blossom. Really trite stuff that’s almost painful to say, but it’s true: awareness is the substance of life, so in a meaningful sense, your ability to see things—in the way someone stands or tells a story or the way a tree moves in the wind—is the building block of your whole life. Though this will be shaped by your chosen discipline (an architect may notice different things than a comedian), the world will become more interesting as you become more interesting.

The more your life approximates a character from Wall-E, the more you will need the spoon-fed stimulation those characters crave.

One reason I love The Artist’s Journey is that her definition of art is expansive. It’s really about overcoming inhibitions in all areas of life, not just the ones keeping you from throwing pottery or writing a one-man play. There are all sorts of clues for what your creative dream may be: what do you pursue in your free time, what dreams are you embarrassed to share, who do you secretly envy?

While our utilitarian, hyper-competitive culture might tempt you to treat those dreams like start-up investments in yourself, I think they’re much closer to exercise.

Do you have to do them? No. Will there likely be someone better than you? Yes, almost certainly. Will you get paid, get famous, or get praised for this? No, probably not. So what’s in it for you?

A chance to be more physically and psychologically balanced. Greater engagement and enjoyment across all of your life. A sense of accomplishment and identity outside of the typical. The reward and self-insight that comes with doing hard things. Feeling alive.

And that’s just the start.

So…